Between the smallpox epidemic and the war of independence: Joseph Warren (1741–1775) as physician and politician

HISTORICAL NOTE

Between the smallpox epidemic and the war of independence: Joseph Warren (1741–1775) as physician and politician

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2025.583

- Education

- Published: 16/08/2025

- Received: 13/08/2025

- Accepted: 13/08/2025

- Views: 4075

- Downloads: 1361

- Keywords: Joseph Warren, smallpox, vaccination, Boston, 18th-century medicine, American RevolutionJoseph Warren, smallpox, vaccination, Boston, 18th-century medicine, American Revolution

Address for Correspondence: Ihor Romaniuk – Ukrainian-Polish Heart Center "Lviv", Lviv, Ukraine

Uliana Pidvalna – Department of Normal Anatomy of the Medical Faculty №1, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine. R&D, Ukrainian-Polish Heart Center "Lviv", Lviv, Ukraine

Email: zahloba91@gmail.com; pidvalna_uliana@meduniv.lviv.ua Phone: +38(099)0930037

ORCID: Ihor Romaniuk - 0009-0005-2811-651X Uliana Pidvalna - 0000-0001-7360-8111

Ihor Romaniuk1, Uliana Pidvalna1,2.

1 Ukrainian-Polish Heart Center "Lviv", Lviv, Ukraine

2 Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine

Abstract

Joseph Warren (1741–1775) – an American physician, surgeon, public figure, and general who played a crucial role in the development of medicine in colonial America in the 18th century and in the events leading up to the American Revolutionary War. This article highlights Dr. Warren’s medical work, including his involvement in the smallpox inoculation campaign during the 1764 epidemic in Boston, his early engagement in obstetric practice, and his contributions to the reform of medical training. It also explores his political activism, particularly his role in drafting the Suffolk Resolves, as well as his heroic death at the Battle of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775, Charlestown, Massachusetts). Special attention is given to Warren’s contribution to the advancement of public health and the shaping of the patriotic physician archetype in U.S. history. His life exemplifies the integration of medicine, morality, and civic duty during a time of profound social transformation.

Key words: Joseph Warren, smallpox, vaccination, Boston, 18th-century medicine, American Revolution

(Heart Vessels Transplant 2025; 9: doi: 10.24969/hvt.2025.583)

![]()

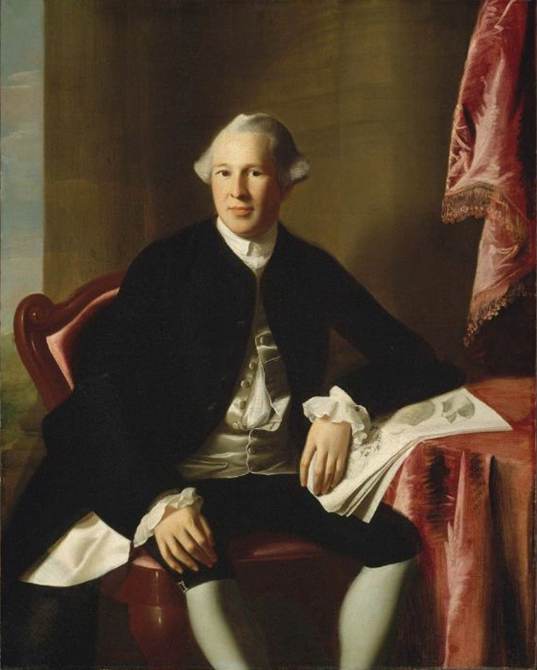

Joseph Warren (1741-1775) (Fig.1) – an American physician, public figure, and general who, as a progressive surgeon, was elected in 1774 а president of the Provincial Congress and chairman of the Committee of Public Safety, the most important Revolutionary political organizations in the state. Warren was an extremely important leader – Grand Master (what we would call president) of Freemasons in North America.

Joseph Warren was born in 1741 in Roxbury, Massachusetts, U.S. After graduating from Harvard College in 1759, he taught at a Latin school and began studying medicine. He started his own medical practice at the age of 23 in Boston, where he practiced both surgery and general medicine.

Warren studied medicine under Boston’s physician, James Lloyd (March 24, 1728 – March 14, 1810), who trained him in modern medical practices and introduced him to prominent Boston families (1). At that time, American physicians did not practice in narrow specialties. Until the mid-19th century, most doctors in the U.S. provided a wide range of available medical services. Lloyd taught Warren the skills of surgery, obstetrics, and general medicine.

Physicians of the era considered themselves essential to the protection of public welfare. Joseph Warren fully understood and embraced his role as a guardian of the community’s well-being (1).

This sense of civic duty was most clearly demonstrated in Warren’s well-documented efforts during the smallpox inoculation campaigns, as well as his care for the wounded following the Boston Massacre (March 5, 1770).

Unlike many Boston physicians of his time, Warren personally provided a wide range of medical services to his patients, including obstetric care for pregnant women. At that time, there was no formal specialization in obstetrics. In the 18th century, childbirth assistance was typically the domain of midwives, and male physicians rarely participated to help pregnant women (2). However, in Warren’s case, there is documented evidence of his involvement in caring for a female patient named Sally Edwards.

Figure 1. Joseph Warren. A portrait by John Singleton Copley, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Republished in frame of CC-BY-SA 4.0 license from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:JosephWarrenByCopley.jpeg)

He arranged medical assistance for her while residing with his friend and colleague Dr. Nathaniel Ames (1708–1764) of Dedham. In 1775, several women named Sally Edwards lived in Boston and its surrounding areas, and it is not definitively known which one Warren was arranging obstetric care for (3).

Smallpox epidemics struck Boston multiple times throughout the 1700s, with the outbreaks of 1721, 1752, 1764, and 1775 being particularly severe. The mortality rate reached around 15%, and survivors often endured tremendous suffering. Observations that those who had survived smallpox rarely contracted it again — and if they did, the infection tended to be mild – led to the development of inoculation as a method of inducing immunity and preventing epidemics.

Inoculation was introduced to Boston by Dr. Zabdiel Boylston (1679–1766) during the 1721 outbreak. Reverend Cotton Mather (1663–1728), who had learned about smallpox inoculation from his West African slave Onesimus, persuaded Dr. Boylston to attempt the procedure (4). At that time, inoculation provoked even greater public outrage and opposition than it sometimes does today – largely due to fatalities associated with the procedure and resistance from the clergy, who believed that smallpox was a divine punishment for sin and that preventing the disease interfered with God's will.

After being arrested for his efforts, Boylston traveled to England, where he reported that only 6 out of the 247 people he had inoculated had died – a mortality rate of just 2.4%, nearly ten times lower than among those who remained unprotected.

By the time of the 1764 smallpox epidemic, inoculation had become more widely accepted. Governor Bernard (1712-1779) ordered the formation of a group of physicians to organize the inoculation of Boston residents. The young and ambitious surgeon Joseph Warren was among the doctors who, at great personal risk, carried out the inoculations (5). He was joined by his mentor and teacher James Lloyd, as well as Benjamin Church (1734-1778) – both well-known surgeons. The inoculations were conducted at a hospital on Castle William, an island near Boston.

Joseph Warren and his former apprentice Samuel Adams, Jr., a political moderate and British army surgeon James Latham to propose a 21-year agreement to establish a smallpox inoculation hospital at Point Shirley, pending approval from the town of Chelsea. Additionally, Warren, Bulfinch, and Latham formed a separate 21-year partnership aimed at founding similar hospitals in other northern colonies, from Pennsylvania upward (6, 7).

An inoculation doctor would deliberately insert a thread soaked in live smallpox matter into a small incision in the patient's skin, intending to induce a controlled infection. This method typically resulted in a milder form of the disease compared to naturally contracted smallpox. The procedure posed a danger not only to the individual but also to the wider community. Someone with a mild case after inoculation might feel well enough to move about town, unknowingly spreading the disease to others who could develop far more severe infections (8).

In 1764, Warren inoculated John Adams, the future second President of the United States. Warren vaccinated a large portion of Boston’s population against smallpox before he was killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775.

Also, it is reasonable to assume that Joseph Warren, as a well-regarded and ambitious student of Lloyd, also engaged in obstetrical practice. The effort by Boston physicians to assume control over the city’s profitable routine obstetric care (traditionally handled by midwives) was initiated by James Lloyd in the 1750s. However, it was not until the 1760s that his reasoning and example began to significantly influence others, particularly his students, leading to a notable decline in the midwives’ role (9). Lloyd’s fees at this time indicate that midwifery could indeed be profitable.

The 1760’s, when James Lloyd and his protégé, Joseph Warren, rose to preeminence among Boston’s medical preceptors, that these improvements became well established. Between 1760 and 1775 these two trained ten (or better than one-fifth) of Boston’s physicians of the era 1760-1790, including such leaders as John Clark VI (1753–1788, physician), William Eustis (1753–1825, regimental surgeon during the American Revolutionary War and statesman from Massachusetts), John Jeffries (1744-1819, physician, scientist, and military surgeon, who was one of the first human beings who crossed the English Channel by air in a balloon), Lemuel Hayward Jr. (1749-1821, President of the Massachusetts Medical Society), Isaac Rand (1743–1822 completed the work initiated by James Lloyd in shifting obstetric practice from midwives to trained physicians), David Townsend (1753–1829 was in charge at the U.S. Marine Hospital in Chelsea, Massachusetts), and John Warren (1753-1815, professorship of anatomy and surgery, who had performed one of the first abdominal operations in this country and was known for his amputations of the shoulder joint) (10-13).

As a politician, Joseph Warren is known as the author of the Stamp Act law, the drafter of the Suffolk Resolves, a member of the committee that demanded the withdrawal of British troops from Boston after the "Massacre," served as chairman of the Committee of Safety, was chairman of the committee responsible for organizing the army in Massachusetts, and was the Grand Master of the Freemasons of Continental America (1). Warren, as an orator, participated annually in the anniversary of the Boston Massacre, and in 1772, he served as the main speaker. His speech has been preserved in many American Revolutionary prose works.

Joseph Warren was killed during the Battle of Bunker Hill (fought largely on Breed’s Hill) on June 17, 1775. When General Israel Putnam (1718-1790) offered Warren command, Warren replied, “I am here only as a volunteer. I know nothing of your orders, and I shall not interfere with them. Tell me where I can be most useful”. Soon after, while covering the retreat of American soldiers, he was shot in the head by a musket ball and died from the wound.

Figure 2. The death of General Warren. Painting by John Trumbull, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Republished in frame of CC-BY-SA 4.0 license rules https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cf/The_Death_of_General_Warren_at_the_Battle_of_Bunker%27s_Hill.jpg)

It is known that one of the earliest postmortem body identifications was carried out on the remains of Joseph Warren. Paul Revere identified Warren’s body several months after his death at the Battle of Bunker Hill by recognizing a tooth (or teeth) he had placed in Warren’s mouth. This is considered one of the first documented cases of forensic dentistry – the identification of a body through dental work (14). His body was reinterred several times in the following years, most recently in 1856, when it was moved to Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain. Had he survived the war, he would likely have become a leading figure in American medicine.

Dr. Joseph Warren was one of the most influential leaders of the early American Revolution, although he is largely forgotten today. For a time, Dr. Warren was among the most famous men in America, famous even more so than George Washington. But due to his short service (he died at age 34), today he is largely forgotten. Joseph Warren’s significant contribution to American history is also evidenced by the fact that, following his death, the Continental Congress ordered that Warren’s children “should be educated at the public expense” until the youngest reached adulthood.

Peer-review: Internal

Conflict-of-interest: None to declare

Authorship: I.R., U.P. equally contributed to the study and fulfilled authorship criteria

Acknowledgement and Funding: None to declare

Statement on A.I.-assisted technologies use: LLMs were used for grammar and spelling correction. After language correction with AI tools, the manuscript was proofread by the authors.

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable

References

| 1.Wildrick GC. Dr. Joseph Warren: Leader in medicine, politics, and revolution. Baylor Univ Medl Center Proc 2009; 22: 27-9. Doi: 10.1080/08998280.2009.11928466 https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2009.11928466 PMid:19169397 PMCid:PMC2626357 |

||||

| 2.Loudon I. General practitioners and obstetrics: a brief history. J R Soc Med 2008; 101: 531-5. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.080264 https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2008.080264 PMid:19029353 PMCid:PMC2586862 |

||||

| 3.Uhlar, J. Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the true story? J Am Revolut 2025. Retrieved from All Things Liberty. Available at: URL: https://allthingsliberty.com/2025/07/joseph-warren-sally-edwards-and-mercy-scollay-defamation-through-unsubstantiated-inferential-leaps/ | ||||

| 4.Hasselgren P-O. The smallpox epidemics in America in the 1700s and the role of surgeons: Lessons to Be learned during the global outbreak of COVID-19. World J Surg 2020; 44: 2838. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05670-4 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05670-4 PMid:32623571 PMCid:PMC7335227 |

||||

| 5.Di Spigna C. (2019). Founding martyr: the life and death of Dr. Joseph Warren, the American Revolution's lost hero. Crown; Crown Publishing Group 2019. | ||||

| 6.The Colonial Society of Massachusetts. The Professionalization of Boston Medicine, 1760-1803. The Colonial Society of Massachusetts. Available at: URL: https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/1202 Accessed July 30, 2025. | ||||

| 7. Forman S. Dr. Joseph Warren: The Boston Tea Party, Bunker Hill, and the Birth of American Liberty. Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., 2011. | ||||

| 8.History.com Editors. How Smallpox Changed America's Course: George Washington and the Revolutionary War. History. Available at: URL: https://www.history.com/articles/smallpox-george-washington-revolutionary-war | ||||

| 9.Certificate of Attendance by James Lloyd at two Courses on Midwifery by William Smellie, BMS Miscellany. Countway Library, Harvard Medical School. | ||||

| 10.Jameson EM. Eighteenth century obstetrics and obstetricians in the United States. Ann Med Hist 1813; 10: 413-32. | ||||

| 11.Notice of the late James Lloyd, M.D. New Engl J Med Surg Collat Branch Sci 1813; 2: 127-30. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM181304010020202 |

||||

| 12. Thacher J. American Medical Biography, 2 v. in 1. Boston: Richardson&Lord, Cotton&Bernard; 1827. pp. 359-76. | ||||

| 13.Viets HR. The medical education of James Lloyd in Colonial America. Yale J Biol Med 1958; 31: 1-14. | ||||

| 14.Steblecki EJ. Carved Ivory Denture, Attributed to Paul Revere, Now on Display in the Education and Visitor Center. The Revere House Gazette, no. 132 (Fall 2018). Paul Revere Memorial Association. Available at: URL: https://www.paulreverehouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/PaulRevereHouse_Gazette132_Fall2018.pdf | ||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER