Immediate results of surgical treatment of patients with malignant tumors of the biliopancreatoduodenal region

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Immediate results of surgical treatment of patients with malignant tumors of the biliopancreatoduodenal region

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2025.617

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 14/12/2025

- Received: 20/10/2025

- Revised: 02/12/2025

- Accepted: 02/12/2025

- Views: 704

- Downloads: 346

- Keywords: pancreatic cancer, duodenal cancer, pancreatoduodenectomy, Whipple procedure, delayed gastric emptying, pancreatic fistula, adenocarcinoma, pancreaticogastrostomy.

Address for Correspondence: Farida S. Rakhimova, Department of Innovative Surgical Technologies,

Kyrgyz State Medical Academy named after I.K. Akhunbaev, 92 I.K. Akhunbaev Street, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

E-mail: farida-0209@mail.ru Phone: +996 556 801 802

ORCID: 0000-0003-3531-8556 Facebook: @farida.rahimova.7

Farida S. Rakhimova

Department of Innovative Surgical Technologies, Kyrgyz State Medical Academy named after I.K. Akhunbaev, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Abstract

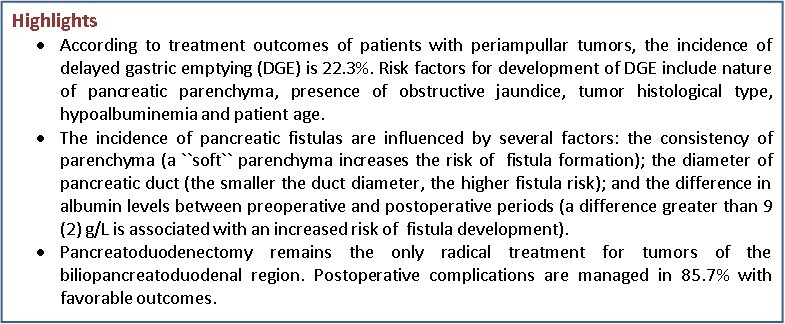

Objective: Pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) is considered one of the most technically demanding procedures in abdominal surgery. This operation is associated with a high risk of postoperative complications, ranging from 30% to 60%. One of the most common complications is delayed gastric emptying (DGE). Although DGE is not a life-threatening complication, it causes significant patient discomfort, prolongs hospital stay, increases treatment costs, leads to repeated hospitalizations, and delays the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Our aim was to evaluate the outcomes of surgical treatment of patients with malignant tumors of the biliopancreatoduodenal region in Kyrgyzstan at a single center.

Methods: This was a retrospective study. The study was conducted at the I.K. Akhunbaev Clinic of the National Hospital under the Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic, Bishkek. Between 2009 and 2024, a total of 90 PDs were performed for malignant neoplasms of the biliopancreatoduodenal region. The study cohort consisted of 70 men and 20 women, with a mean age of 57.5 (1.4) years. We assessed patients` outcomes as postoperative complications and mortality after surgery.

Results: Postoperative complications occurred in 26 patients (28.8%). The most severe complications included pancreaticogastrostomy leakage with pancreatic fistula formation in 6 patients (6.7%), biliodigestive anastomosis leakage in 1 patient (1.1%), delayed gastric emptying in 20 patients (22.2%), gastroenteroanastomosis leakage in 3 patients (3.3%), and pulmonary embolism in 1 patient (1.1%). Reoperation was required in three cases. Postoperative mortality was 3.6%.

Conclusion: At present, pancreatoduodenectomy remains the only radical treatment for tumors of the biliopancreatoduodenal region. Postoperative complications were observed in 28.8% of patients. In 85.72% of cases, complications were managed conservatively with favorable outcomes.

Key words: pancreatic cancer, duodenal cancer, pancreatoduodenectomy, Whipple procedure, delayed gastric emptying, pancreatic fistula, adenocarcinoma, pancreaticogastrostomy.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Gastropancreatoduodenal resection is considered one of the most technically demanding operations in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery and is the standard approach for resectable periampullary neoplasms (1). These tumors carry a poor prognosis and rank among the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Known risk factors for biliopancreatoduodenal carcinomas include older age, smoking, and alcohol consumption, family history of chronic pancreatitis, familial adenomatous polyposis, and genetic predisposition (2).

In most patients, the tumor is diagnosed at an advanced stage; only approximately 10–20% of patients are candidates for potentially curative resection at presentation. Multimodal oncological treatment remains the mainstay for improving long‑term survival, and gastropancreatoduodenal resection with formal regional lymphadenectomy is considered the operation of choice for resectable disease (3, 4).

The procedure is associated with a substantial risk of postoperative complications, with reported rates ranging between 30% and 60%. Major complications include hemorrhage, pancreatic fistula, biliary leak, and delayed gastric emptying (DGE) (5). In high‑income countries, the frequency of severe complications has declined due to advances in surgical technique and perioperative care; however, healthcare systems in low‑ and middle‑income countries often face resource limitations that impede provision of optimal perioperative management (3, 4).

Over the past decade postoperative mortality following pancreaticoduodenectomy has decreased from approximately 25% to under 5% in many centers; nevertheless, 5‑year survival after resection remains limited (approximately 10–20%) (6).

In the Kyrgyz Republic, cancers of the biliopancreatoduodenal zone rank sixth among all oncological diseases.

Late presentation and advanced tumor stage at diagnosis result in poor survival, with many patients succumbing within an average of 6–8 months from diagnosis. Implementation of gastropancreatoduodenal resection in Kyrgyzstan began in 2009 when our surgical team performed the country’s first such operation. Since then, efforts have focused on early detection and expansion of access to radical surgical treatment.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate To evaluate the outcomes of surgical treatment of patients with malignant tumors of the biliopancreatoduodenal region (BPDR) in the Kyrgyz Republic and to determine the relationship between the development of postoperative complications and factors such as the duration of surgery, the use of external biliary drainage, and the characteristics of the pancreatic parenchyma.

Methods

Study design and population

This study is a retrospective cohort study. All patients who received inpatient treatment for neoplasms of the BPDR region were analyzed. This study is based on the analysis of the immediate results of surgical treatment of patients with malignant neoplasms of the BPDR region. Clinical data were collected in the Department of Surgical Gastroenterology and Endocrinology of the National Hospital under the Ministry of Health of the Kyrgyz Republic over the period from 2009 to 2024. During this time, 325 patients with histologically confirmed malignant lesions of the BPDR received treatment.

All patients included in the study provided written informed consent for treatment. In our institution, Ethical Committee approval is not required for retrospective studies.

Baseline variables

We collected demographic data as age and sex of patients, clinical presentation and symptoms, the type of the first medical facility patients sought care, tumor stage, tumor type and type of surgery, histological type of tumor.

We analyzed intraoperative data as tumor consistency on palpation and intraoperative blood loss; postoperative variables including complaints (nausea, vomiting), presence of infection, presence of drainage from wound, evaluation of drain amylase and protein level,; bleeding, need for nasogastric tube with duration, need for nutritional support, start of oral intake of food; diagnostic methods for complications as X-RAY of upper gastrointestinal tract with barium, computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Surgery

The management strategy was determined by the tumor stage, the patient’s general condition, and the feasibility of performing radical surgery.

Resectable pancreatic head cancer was defined as a non-metastatic tumor that does not involve the superior mesenteric artery, celiac trunk, or superior mesenteric/portal veins, or demonstrates ≤180° contact with the superior mesenteric vein and/or portal vein without contour irregularities. Attention was also given to the general clinical condition: acceptable performance status (ECOG 0–2), moderate anesthetic risk (ASA I–III), and adequate cardiopulmonary and hepatic function to tolerate major surgery.

Pancreatoduodenectomy with R0 resection was performed in 90 patients, as confirmed by postoperative histopathological examination. The remaining 240 patients received palliative treatment due to locally advanced disease and the technical impossibility of performing radical surgery. Palliative procedures were aimed at relieving biliary or duodenal obstruction and included biliodigestive and gastroenteric anastomoses, as well as percutaneous transhepatic cholangiostomy. Additionally, patients were referred to the National Center of Oncology and Hematology for adjuvant chemotherapy.

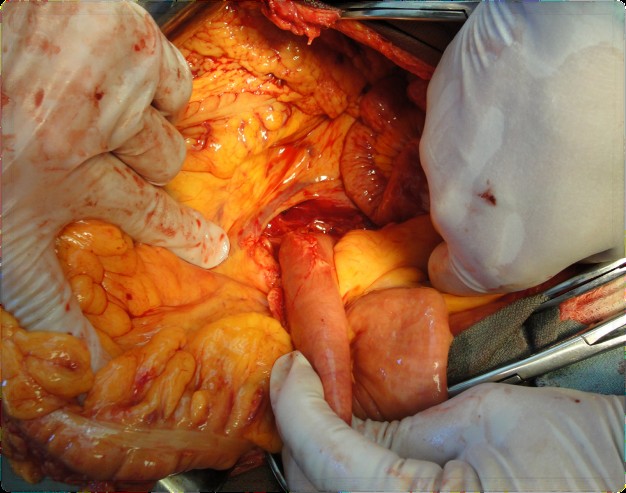

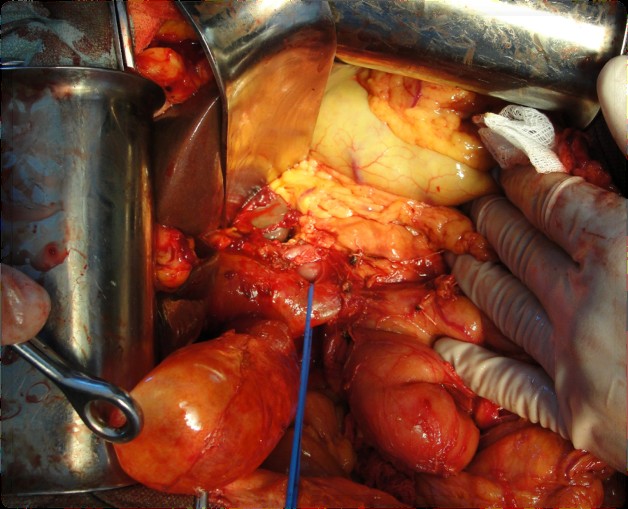

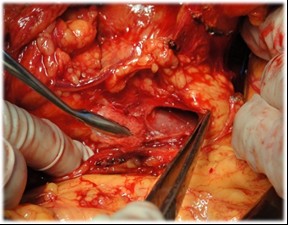

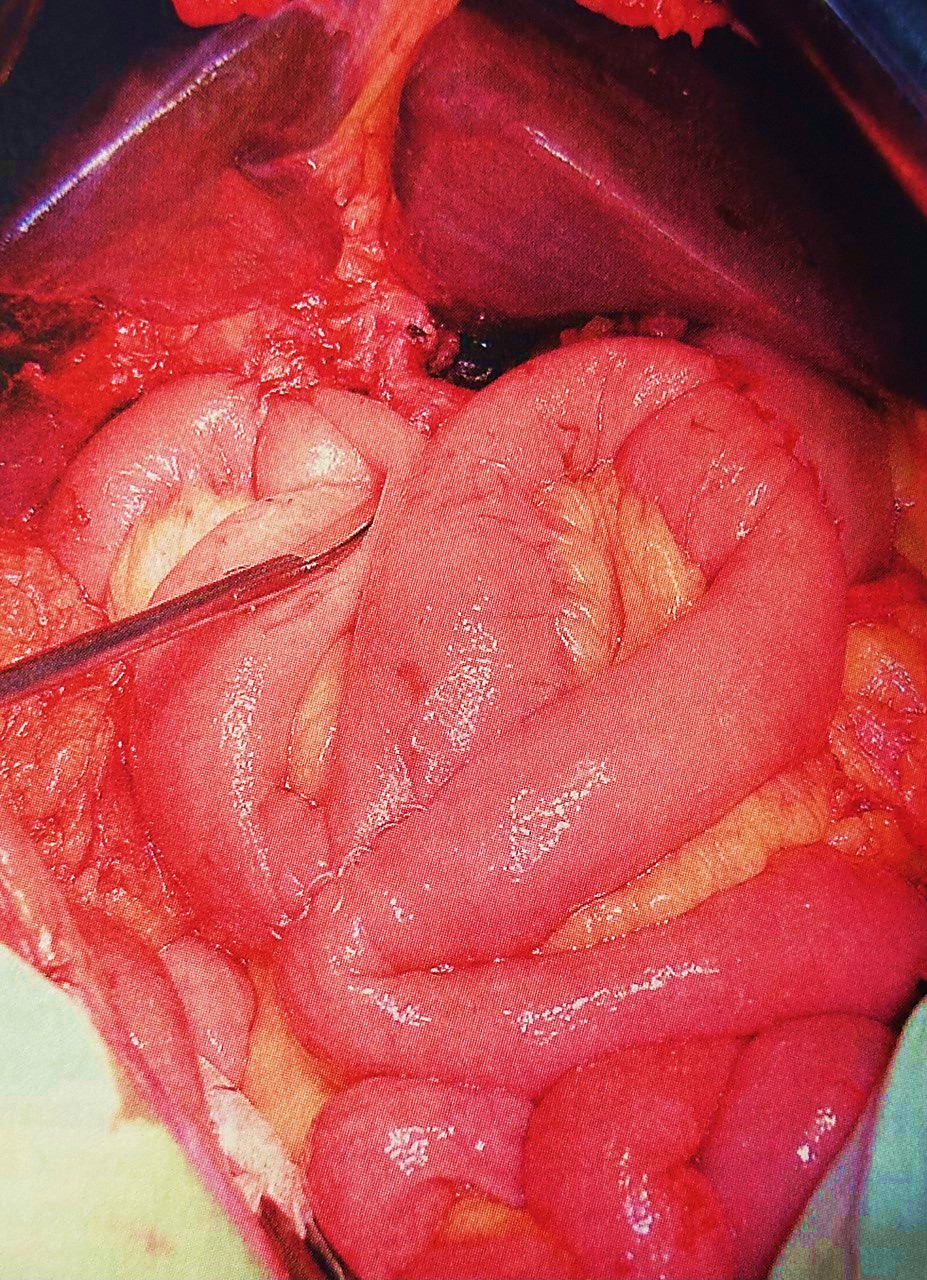

The pancreatoduodenal resection included the following steps: mobilization of the organs of the BPDR (Figs. 1–2); dissection of the hepatic portal structures (Fig. 3); and creation of a retropancreatic tunnel for subsequent resection of the pancreatic head (Fig. 4). The reconstructive phase consisted of the formation of a pancreaticogastrostomy (Fig. 5), a hepaticojejunostomy (Fig. 6), and a gastrojejunostomy with a Braun enteroenterostomy (Fig. 7).

Figure 1. Dissection of the organ of the biliopancreatoduodenal region

Figure 2. Mobilization and dissection of the duodenum

Figure 3. Dissection of the common bile duct

Figure 4. Direct mobilization of the pancreatic head and creation of a retropancreatic tunnel for subsequent resection

Figure 5. Reconstructive phase: creation of the hepaticojejunostomy

Figure 6. Reconstructive phase: creation of the pancreaticogastrostomy

Figure 7. Construction of the gastroenterostomy with Braun enteroenterostomy

Outcomes

We assessed immediate postoperative complications as gastroparesis, pancreaticogastrostomy leakage with pancreatic fistula formation, biliodigestive anastomosis leakage, delayed gastric emptying, gastroenteroanastomosis leakage, pulmonary embolism and mortality.

Gastrostasis is a disorder of gastric emptying that frequently complicates the postoperative course in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy. Gastroparesis following pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy was first described by A. Warshaw and D. Torchiana in 1985 (7). In 2007, the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS), which includes experts from leading pancreatic surgery centers worldwide, proposed a standardized definition of delayed gastric emptying (DGE) (8): DGE is the requirement of nasogastric tube after postoperative day 3 or failure to resume and oral diet by postoperative day 7. According to this classification, three grades of DGE are distinguished: A, B, and C based on day of nasograstric tube removal (none <3 days, A- 4-7 days, B – 8-14 days and c≥15 days); it reinsertion (none, ≥3 days, ≥7 days, ≥14 days); inability to tolerate solid oral intake (-, 7-13 days, 14-20 days, ≥21 days, presence of nausea, vomiting, use of prokinetics, association with other complications, use of diagnostic methods – upper gastrointestinal tract with barium X-Ray, ultrasound, CT).

By ISGPS definition, a postoperative pancreatic fistula is defined as a drain output of fluid with an amylase level greater than three times the upper limit of normal serum amylase activity, measured on or after postoperative day 3, and associated with a clinically relevant impact on the patient’s postoperative course (9). Pancreatic fistula (ISGPF) grading is as following - no fistula, grades A, B and C and is based on: presence of amylase in drain output (No, >3x normal value for all A, B, C grades, clinical condition, specific treatment, positive ultrasound/CT, presence of persistence drainage, signs of infection, readmission, sepsis, reoperation, and death related to fistula (9).

According to ISGPS recommendations (10), pancreatic gland consistency is determined intraoperatively based on palpation, visual assessment of the degree of fibrosis, and the diameter of the main pancreatic duct. A soft pancreas is characterized by elastic parenchyma and a narrow duct (<3 mm), whereas a firm pancreas is defined by the presence of fibrosis and a dilated duct (>3–4 mm). The diameter of the main pancreatic duct was assessed based on MRI findings.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the study results was performed using a personal computer. For comparative evaluation, IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 software (New York, USA) was employed to calculate mean values (M) and standard errors of the mean (m). All research data were entered into a computerized database and analyzed using SPSS and Microsoft Excel analytical tools. The categorical variables were compared using Chi-square or Fischer exact test, continuous using Mann-Whitney U test. The p <0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients

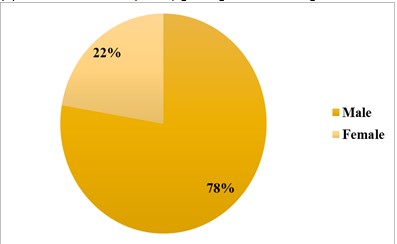

Among the 90 patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy, 70 (77.8%) were men and 20 (22.2%) were women (Fig. 8). The majority of patients being male, suggests a higher prevalence of biliopancreatoduodenal tumors among men.

Figure 8. Distribution of patients by sex

The age of patients ranged from 16 to 81 years, with a mean age of 57.8 (1.5) years (Table 1). The majority of patients were in the middle-aged and elderly groups (85.5%), indicating a correlation between higher disease incidence and older age (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Distribution of patients by age according to the WHO classification (2017) (n = 90) |

||

|

Age group, years |

Number of patients |

% |

|

18–44 (young) |

4 |

4.4 |

|

45–59 (middle-aged) |

38 |

42.2 |

|

60–74 (elderly) |

39 |

43.3 |

|

75–90 (senile) |

9 |

10.0 |

|

Total |

90 |

100 |

Among the 90 patients who underwent surgery for malignant tumors of the BPDR, tumor staging was performed according to the 8th edition of the TNM classification. The distribution by stage was as follows: T2N0M0 (Stage I) — 9 patients (10%); T1-3N0-1M0 (Stage II) — 77 patients (85.5%); T1-3N2M0 (Stage III) — 4 patients (4.4%).

According to the obtained data, in 50 patients (55.5%) the disease initially manifested with obstructive jaundice syndrome. The most common initial symptoms were pain in the right upper quadrant, scleral and skin icterus, acholic stools, and dark urine. The symptoms typically developed and progressed over several weeks, often leading patients to initially seek medical care at non-specialized healthcare facilities rather than surgical centers.

According to our data, 15 patients (17.6%) first presented to infectious disease hospitals, from which they were referred to surgical departments after additional diagnostic work-up, resulting in a delay in establishing the final diagnosis. Another 25 patients (29.4%) initially presented to primary care or family medicine centers in their local communities, where they received inappropriate treatment for an average of 17 (10) days before being referred for specialized care.

Outcomes

We analyzed the immediate and early postoperative period outcomes in the patients. Postoperative complications were observed in 26 patients, with a total of 31 complications (34.4%). They included: pancreaticogastrostomy leakage with pancreatic fistula formation — 6 patients (6.7%); biliodigestive anastomosis leakage — 1 patient (1.1%); DGE — 20 patients (22.2%); gastroenteroanastomosis leakage — 3 patients (3.3%); pulmonary embolism — 1 patient (1.1%)

Early postoperative mortality was recorded in 3 patients, corresponding to a postoperative mortality rate of 3.3%. In one case, the cause of death was pulmonary embolism. In the other two cases, the leading cause was multiple organ failure secondary to gastroenteroanastomotic leakage and subsequent peritonitis.

Intraoperative blood loss ranged from 100 to 760 mL, with a mean volume of 450 mL. The duration of surgical procedures varied between 250 and 480 minutes, with a mean operative time of 356 minutes.

According to histological examination of the resected specimens, the morphological structure of the tumors was distributed as follows: pancreatic adenocarcinoma — 59 patients (65.5%); duodenal adenocarcinoma — 5 patients (5.6%); ampullary adenocarcinoma — 12 patients (13.3%); cholangiocarcinoma of the common bile duct — 7 patients (7.7%); pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors — 4 patients (4.4%); solid pseudopapillary tumors (Frantz tumors) — 2 patients (2.2%); and retroperitoneal lymphosarcoma — 1 patient (1.1%).

Thus, pancreatic adenocarcinoma was the most common histological type, which is consistent with global epidemiological data.

Particular attention was given to complications such as DGE and pancreatic fistula, as they were the most frequent postoperative complications in our study. Therefore, it is appropriate to provide a more detailed analysis of their incidence, clinical course, and the conservative management strategies employed in our practice.

According to the classification criteria used to grade the severity of DGE, all patients were assigned to groups based on the degree of the complication (Table 2).![]()

|

Table 2. Severity of delayed gastric emptying (n= 20) |

|||

|

Grade |

Number of patients |

% |

|

|

Grade A |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Grade B |

17 |

85 |

|

|

Grade C |

3 |

15 |

|

|

Total |

20 |

100 |

|

In the overall structure of postoperative complications, Grade B DGE predominated, occurring in 85% of patients in this group. According to our observations, DGE developed most frequently in patients with pancreatic head tumors (16 cases), less commonly in patients with ampullary carcinoma (3 cases), and rarely in patients with distal common bile duct cancer (1 case).

Additionally, an analysis was conducted to investigate the relationship between the development of DGE and the histological type of the tumor. The results are presented in Table 3.

|

Table 3.Distribution of delayed gastric emptying according to tumor localization and histological type |

|||

|

Histological type |

Pancreatic head |

Ampulla of Vater |

Distal common bile duct |

|

Adenocarcinoma, n(%) |

13 (65) |

3 (15) |

1 (5) |

|

Neuroendocrine tumor, n(%) |

3 (15) |

— |

— |

As shown in Table 3, the highest incidence of DGE was observed in patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head, accounting for 65% of all DGE cases. Notably, among the four patients with neuroendocrine tumors, three developed DGE, suggesting a possible predisposition of this histological tumor type to the development of this complication.

Additionally, an analysis was performed to assess the incidence of postoperative DGE according to patient age (Table 4). Among the 20 cases of DGE, 14 patients (70%) were in the middle-aged group (45–59 years) according to the WHO classification.

|

Table 4. Distribution of patients by age and occurrence of delayed gastric emptying (n = 20) |

||

|

Age group, years |

Number of patients |

% |

|

18–44 (young) |

0 |

0 |

|

45–59 (middle-aged) |

14 |

70 |

|

60–74 (elderly) |

6 |

30 |

|

75–90 (senile) |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

20 |

100 |

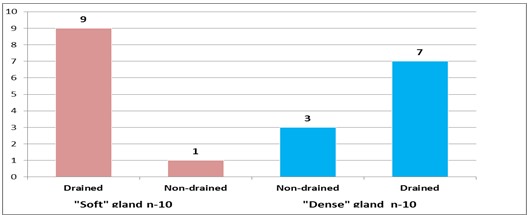

We also analyzed patients with DGE according to the condition of the pancreatic parenchyma (Fig. 9). This assessment plays a crucial role in predicting the risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula.

Figure 9. Distribution of patients with delayed gastric emptying according to the condition of the pancreatic parenchyma

As see in the diagram, the largest proportion — 9 patients (45%) with DGE — had a “soft” pancreas and developed obstructive jaundice, which was followed by external biliary drainage.

Subsequently, we analyzed the relationship between the development of DGE and the condition of the pancreatic parenchyma (Table 5).

|

Table 5. Correlation between the development of delayed gastric emptying and pancreatic parenchymal characteristics |

|||

|

Characteristics |

“Soft” pancreas (n = 34) |

“Firm” pancreas (n = 62) |

p |

|

Drainage |

|

||

|

– Drained |

9 |

7 |

0.03 |

|

– Not drained |

1 |

3 |

|

|

By nosology |

|

||

|

– Pancreatic head cancer |

5 |

7 |

0.26 |

|

– Ampullary cancer |

3 |

– |

0.34 |

|

– Distal bile duct cancer |

1 |

– |

0.29 |

According to the analysis, the highest incidence of DGE was observed in patients with a “soft” pancreatic parenchyma who had undergone preoperative external biliary drainage for obstructive jaundice. Also, among firm pancreas the majority was drained. The findings demonstrated a statistically significant relation between the occurrence of DGE and the presence of preoperative obstructive jaundice requiring external biliary drainage (p=0.03).

Postoperative amylase levels were also analyzed among patients who developed DGE. Only four patients showed a moderate increase—approximately 1.5-fold above the normal range. Notably, none of these patients had undergone preoperative external biliary drainage. It is important to emphasize that starting from the time of pancreatic surgery, all patients routinely received subcutaneous somatostatin analogue (Sandostatin) at a dose of 0.1 mg every 8 hours for five days. This protocol likely reduces the risk of clinically significant postoperative pancreatitis and, consequently, may mitigate any direct statistical association between postoperative amylase levels and the development of DGE.

Protein metabolism parameters were additionally assessed in patients with DGE. A reduction in total serum protein to 57–58 g/L in the postoperative period was observed in only two patients. Although most patients maintained total protein levels within the reference range, hypoalbuminemia was detected in 13 patients (65%), with a mean albumin level of 27 (2) g/L.

An interesting observation emerged when DGE incidence was compared across blood groups. The highest rates were found among patients with blood group II (50%) and blood group III (35%), which may suggest a potential predisposition of these groups to the development of DGE—an association that warrants further investigation (Table 6).

|

Table 6.Blood group distribution of patients |

||||||

|

Blood group |

O (I) |

A (II) |

B (III) |

AB (IV) |

||

|

Number of gastrostases |

n |

1 |

10 |

7 |

2 |

|

|

% |

5 |

50 |

35 |

10 |

||

DGE management

The conservative management of DGE followed a standardized multi-step approach. All patients underwent nasogastric tube placement for gastric decompression. Pharmacologic stimulation of gastrointestinal motility was performed using anticholinesterase agents, complemented by the administration of the macrolide antibiotic erythromycin—the only drug with a direct prokinetic effect on the stomach. In most patients, nasogastric output began to decrease by postoperative day 3, and complete resolution of DGE typically occurred within 7–10 days of treatment.

The second most common complication observed in our practice was pancreaticogastrostomy failure, occurring in six cases (Table 7).

A correlation analysis was also conducted to evaluate the association between the development of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF), pancreatic parenchymal characteristics, and the presence of preoperative external biliary drainage. POPF developed in 4 of 6 patients with a “soft” pancreatic texture, whereas only 2 cases occurred in patients with a “firm” pancreas. Notably, all four patients in the “soft” pancreas group had not undergone preoperative external biliary drainage, indicating the absence of obstructive jaundice prior to surgery.

|

Table 7. Distribution of patients according to the type of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) |

|||

|

Type of POPF |

Biochemical leak |

Grade B |

Grade C |

|

Number of patients |

– |

5 |

1 |

Furthermore, a significant relation was identified between POPF occurrence and the diameter of the main pancreatic duct (Wirsung’s duct) (Table 9). The data showed that a smaller duct diameter was associated with a higher risk of pancreatic fistula formation (p< 0.05).

|

Table 9. Characteristics of patients according to pancreatic texture |

||||

|

Pancreatic Texture |

Drained (mm) |

Not Drained (mm) |

Pp (Drained vs Not Drained) |

p (Soft vs Firm) |

|

Soft |

– |

2.8 ± 0.3 |

– |

– |

|

Firm |

8 |

5 |

0.04* |

0.03* |

These findings suggest that the absence of preoperative obstructive jaundice or reactive pancreatitis, in combination with soft pancreatic texture and a narrow pancreatic duct are risk factors for the development of POPF.

Management strategy of POPF

All patients who developed POPF received synthetic somatostatin analogues. In most cases, clinical improvement was observed, with spontaneous fistula closure occurring between postoperative days 21 and 30, followed by the removal of drainage tubes. Reoperation was required in only one case due to increasing pancreatic effluent output. In this patient, the initial pancreaticogastrostomy was revised to an end-to-end invagination pancreaticojejunostomy.

The average length of hospital stay among patients who developed postoperative complications was 18 (2.5) days.

Discussion

Pancreaticoduodenal resection remains the only curative surgical option for malignant tumors of the BPDR (11-16). Despite substantial advances in surgical techniques, reconstruction strategies, and perioperative management, the incidence of postoperative complications reported in international literature remains high, ranging from 30% to 60% (17-21). In our study, the overall complication rate was 28.8%, which lies at the lower end of the global range and indicates adequate surgical quality within a national tertiary center.

The postoperative mortality rate of 3.3% in our cohort is comparable to that reported by high-volume international institutions (2–5%) (18-22), reflecting the effectiveness of perioperative anesthetic and intensive care even in the context of resource limitations typical for developing healthcare systems. Moreover, the majority of complications (85.72%) were successfully managed conservatively, underscoring the importance of vigilant postoperative monitoring and a multidisciplinary approach.

A notable finding of this study is that 55.6% of patients initially presented to non-specialized primary care or general surgical facilities. Insufficient oncologic alertness among primary-level physicians in regional hospitals leads to delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the time of referral. This pattern is common in low- and middle-income countries and highlights the need for improved patient referral pathways and enhanced oncologic training for primary care providers.

The incidence of DGE after pancreaticoduodenal resection in our series was 22.2%, consistent with the international ISGPS-based reported range (15–45%) (21-29). We identified a significant association between DGE and preoperative external biliary drainage, a finding that aligns with several international studies suggesting that biliary decompression may impair postoperative gastrointestinal motility.

Furthermore, this study established for the first time in our region a statistically significant relationship between DGE and the morphofunctional characteristics of the pancreas, which opens new avenues for research into the pathophysiology of this complication.

The rate of POPF was 6.7%, which is lower than the generally reported international incidence of 10–30%. The identified correlation between POPF, soft pancreatic parenchymal consistency, and preoperative biliary drainage is well supported by global evidence, as these factors are widely acknowledged predictors of fistula formation. The relatively low POPF rate in our study may reflect the high technical proficiency in creating pancreatic anastomoses and adherence to standardized operative protocols.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that postoperative outcomes after pnacreatoduodenal resection in the Kyrgyz Republic are largely comparable to those reported by specialized high-volume centers worldwide (30-39). At the same time, the unique patient profile characterized by delayed referral, frequent preoperative biliary drainage, and specific pancreatic morphologic features defines a distinct risk landscape that warrants further targeted investigation.

Study limitations

The limitation of the study is relatively small sample size. Future investigations should focus on developing preventive strategies, refining indications for preoperative biliary decompression, and exploring the biological and molecular determinants of postoperative complications. Addressing these factors will contribute to reducing the incidence of the most clinically significant postoperative events following P pnacreatoduodenal resection and enhancing oncologic outcomes for patients in the Kyrgyz Republic.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that pancreaticoduodenal resection can be performed in the Kyrgyz Republic with safety and outcomes comparable to those achieved at leading international centers. The rates of postoperative complications and mortality meet global standards, while the relatively low incidence of POPF is a favorable indicator of surgical and perioperative quality.

The identified associations between preoperative external biliary drainage, pancreatic morphofunctional characteristics, and the development of DGE and POPF underscore the need for further research aimed at elucidating the underlying mechanisms of these complications. Improving oncologic awareness among frontline physicians and optimizing patient referral pathways are essential, given the high proportion of late presentations.

Ethics: All patients included in the study provided written informed consent for treatment. In our institution, Ethical Committee approval is not required for retrospective studies.

Peer-review: External and internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: F.S.R. direct data collection and processing, analyzing and manuscript writing.

Acknowledgements and funding: None to declare

Statement on A.I.-assisted technologies use: We declare that we did not use AI-assisted technologies in preparation of this manuscript

Data and material availability: Contact authors. Any share should be in frame of fair use with acknowledgement of source and/or collaboration.

References

| 1. McGuigan A, Kelly P, Turkington RC, Jones C, Coleman HG, McCain RS. Pancreatic cancer: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24: 4846-61. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i43.4846 PMid:30487695 PMCid:PMC6250924 |

||||

| 2.Changazi SH, Ahmed Q, Bhatti S, Siddique S, Raffay EA, Farooka MW, et al. Whipple procedure: a five-year clinical experience in tertiary care center. Cureus 2020. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.11466 |

||||

| 3.Qiu J, Li M, Du C. Antecolic reconstruction is associated with a lower incidence of delayed gastric emptying compared to retrocolic technique after Whipple or pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98: e16663. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000016663 PMid:31441841 PMCid:PMC6716732 |

||||

| 4.Futagawa Y, Kanehira M, Furukawa K, Kitamura H, Yoshida S, Usuba T, et al. Impact of delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy on survival. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci 2017; 24: 466-74. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.482 PMid:28547910 |

||||

| 5.Griffin JF, Poruk KE, Wolfgang CL. Pancreatic cancer surgery: past, present, and future. Chin J Cancer Res 2015; 27: 332-48. | ||||

| 6.Shabunin AV, Tavobilov MM, Karpov AA. Functional state of the stomach and small bowel after surgery for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann HPB Surg 2016; 21: 62-7. https://doi.org/10.16931/1995-5464.2016262-67 |

||||

| 7.Camilleri M, Chedid V, Ford AC, Haruma K, Horowitz M, Jones KL, et al.. Gastroparesis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4: 41. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0038-z PMid:30385743 |

||||

| 8.Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2007; 142: 761-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2007.02.001 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.005 PMid:17981197 |

||||

| 9. Bassi C, Marchegiani, Dervenis, Sarr M, Hilal MA, Adham M, et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery 2017; 161: 584-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014 PMid:28040257 |

||||

| 10. Schuh F, Mihalevic A, Probst P, Trudeau MT, Muller PC, Marcheghiani G, et al. A simple classification of pancreatic duct size and texture predicts postoperative pancreatic fistula. Ann Surg 2021; 277; e597-e608. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004855 PMid:33914473 PMCid:PMC9891297 |

||||

| 11.Huang W, Xiong JJ, Wan MH, Szatmary P, Bharucha S, Gomatos I, et al. Meta-analysis of subtotal stomach-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy vs pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21: 6361-73. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i20.6361 PMid:26034372 PMCid:PMC4445114 |

||||

| 12.Wu W, Hong X, Fu L, Liu S, You L, Zhou L., Zhao Y. The effect of pylorus removal on delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of 2,599 patients. PLoS One 2014; 9: e108380. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108380 PMid:25272034 PMCid:PMC4182728 |

||||

| 13.Kawai M, Tani M, Hirono S, Miyazawa M, Shimizu A, Uchiyama K, et al. Pylorus ring resection reduces delayed gastric emptying in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of pylorus-resecting versus pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 2011; 253: 495-501. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820d98f1 PMid:21248633 |

||||

| 14.Varghese C, Bhat S, Wang TH, O'Grady G, Pandana Boyana S. Impact of gastric resection and enteric anastomotic configuration on delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a network meta-analysis of randomized trials. BJS Open 2021; 5: zrab035. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zrab035 PMid:33989392 PMCid:PMC8121488 |

||||

| 15.Müller PC, Ruzza C, Kuemmerli C, Steinemann DC, Müller SA, Kessler U, et al. 4/5 gastrectomy in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy reduces delayed gastric emptying. J Surg Res 2020; 249: 180-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2019.12.028 PMid:31986360 |

||||

| 16.Zhou Y, Lin L, Wu L, Xu D, Li B. A case-matched comparison and meta-analysis comparing pylorus-resecting pancreaticoduodenectomy with pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy for the incidence of postoperative delayed gastric emptying. HPB (Oxford) 2015; 17: 337-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/hpb.12358 PMid:25388024 PMCid:PMC4368398 |

||||

| 17.Klaiber U, Probst P, Strobel O, Michalski CW, Dörr- Harim C, Diener MK, et al. Meta-analysis of delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving versus pylorus-resecting pancreatoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 2018; 105: 339-49. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10771 PMid:29412453 |

||||

| 18.Bell R, Pandanaboyana S, Shah N, Bartlett A, Windsor JA, Smith AM. Meta-analysis of antecolic versus retrocolic gastric reconstruction after a pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2015; 17: 202-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/hpb.12344 PMid:25267428 PMCid:PMC4333780 |

||||

| 19.Cao SS, Lin QY, He MX, Zhang GQ. Effect of antecolic versus retrocolic reconstruction for gastro/duodenojejunostomy on delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis. Surg Pract 2014; 18: 72-81. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-1633.12055 |

||||

| 20.Zhou Y, Lin J, Wu L, Li B, Li H. Effect of antecolic or retrocolic reconstruction of the gastro/duodenojejunostomy on delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 2015; 15: 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-015-0300-8 PMid:26076690 PMCid:PMC4467059 |

||||

| 21.Joliat GR, Labgaa I, Demartines N, Schäfer M, Allemann P. Effect of antecolic versus retrocolic gastroenteric reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy on delayed gastric emptying: a meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials. Dig Surg 2016; 33: 15-25. https://doi.org/10.1159/000441480 PMid:26566023 |

||||

| 22.Huang MQ, Li M, Mao JY, Tian BL. Braun enteroenterostomy reduces delayed gastric emptying: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2015; 23 (Pt A): 75-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.09.038 PMid:26384836 |

||||

| 23.Zhou Y, Hu B, Wei K, Si X. Braun anastomosis lowers the incidence of delayed gastric emptying following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 2018; 18: 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0909-5 PMid:30477442 PMCid:PMC6258435 |

||||

| 24.Hwang H, Lee SH, Han DH, Choi SH, Kang CM, Lee WJ. Impact of Braun anastomosis on reducing delayed gastric emptying following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2016; 23: 364-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.349 PMid:27038406 |

||||

| 25.Fujieda H, Yokoyama Y, Hirata A, Usui H, Sakatoku Y, Fukaya M, et al. Does Braun anastomosis have an impact on the incidence of delayed gastric emptying and the extent of intragastric bile reflux following pancreatoduodenectomy? A randomized controlled study. Dig Surg 2017; 34: 462-8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000455334 PMid:28132059 |

||||

| 26.Kakaei F, Beheshtirouy S, Nejatollahi SM, Rashidi I, Asvadi T, Habibzadeh A, et al. Effects of adding Braun jejunojejunostomy to standard Whipple procedure on reduction of afferent loop syndrome - a randomized clinical trial. Can J Surg 2015; 58: 383-8. https://doi.org/10.1503/cjs.005215 PMid:26574829 PMCid:PMC4651689 |

||||

| 27.Xiao Y, Hao X, Yang Q, Li M, Wen J, Jiang C. Effect of Billroth-II versus Roux-en-Y reconstruction for gastrojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy on delayed gastric emptying: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2021; 28: 397-408. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.828 PMid:32897643 |

||||

| 28.Busquets J, Martín S, Fabregat J, Secanella L, Pelaez N, Ramos E. Randomized trial of two types of gastrojejuno stomy after pancreatoduodenectomy and risk of delayed gastric emptying (PAUDA trial). Br J Surg 2019; 106: 46-54. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11023 PMid:30507039 |

||||

| 29.Herrera Cabezón J, Sánchez Acedo P, TarifaCastilla A, ZazpeRipa C. Delayed gastric emptying following pancreatoduodenectomy: a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy vs Billroth II gastrojejunostomy randomized study. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2019; 111: 34-9. https://doi.org/10.17235/reed.2018.5744/2018 PMid:30284910 |

||||

| 30. Shimoda M, Kubota K, Katoh M, Kita J. Effect of Billroth II or Roux-en-Y reconstruction for the gastrojejunostomy on delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a randomized controlled study. Ann Surg 2013; 257: 938-42. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826c3f90 PMid:23579543 |

||||

| 31.Tani M, Kawai M, Hirono S, Okada KI, Miyazawa M, Shimizu A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of isolated Roux-en-Y versus conventional reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 1084-91. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9544 PMid:24975853 |

||||

| 32.Hayama S, Senmaru N, Hirano S. Delayed gastric emptying after pancreatoduodenectomy: comparison between invaginated pancreatogastrostomy and pancreatojejunostomy. BMC Surg 2020; 20: 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00707-w PMid:32245470 PMCid:PMC7118865 |

||||

| 33.Jin Y, Feng YY, Qi XG, Hao G, Yu YQ, Li JT, Peng SY. Pancreatogastrostomy vs pancreatojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: an updated meta-analysis of RCTs and our experience. World J. Gastrointest. Surg 2019; 11: 322-32. https://doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v11.i7.322 PMid:31602291 PMCid:PMC6783689 |

||||

| 34.Palanivelu C, Senthilnathan P, Sabnis SC, Babu NS, Srivatsan Gurumurthy S, Anand Vijai N, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumours. Br J Surg 2017; 104: 1443-50. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10662 PMid:28895142 |

||||

| 35.van Hilst J, de Rooij T, Bosscha K, Brinkman DJ, van Dieren S, Dijkgraaf MG, et al. Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2): a multicentre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 4: 199-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30004-4 PMid:30685489 |

||||

| 36.Poves I, Burdío F, Morató O, Iglesias M, Radosevic A, Ilzarbe L, et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes between laparoscopic and open approach for pancreatoduodenectomy: the PADULAP randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2018; 268: 731-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002893 PMid:30138162 |

||||

| 37.Zhang H, Lan X, Peng B, Li B. Is total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy superior to open procedure? A metaanalysis. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25: 5711-31. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i37.5711 PMid:31602170 PMCid:PMC6785520 |

||||

| 38.Ausania F, Landi F, Martínez-Pérez A, Fondevila C. A metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials comparing laparoscopic vs open pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2019; 21: 1613-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2019.05.017 PMid:31253428 |

||||

| 39.Lin D, Yu Z, Chen X, Chen W, Zou Y, Hu J. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2020; 112: 34-40. https://doi.org/10.17235/reed.2019.6343/2019 PMid:31823640 |

||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER