Transient left ventricular dysfunction consistent with Takotsubo syndrome — A case series

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Transient left ventricular dysfunction consistent with Takotsubo syndrome — A case series

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2025.618

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 14/12/2025

- Received: 16/10/2025

- Revised: 24/11/2025

- Accepted: 24/11/2025

- Views: 996

- Downloads: 359

- Keywords: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, stress cardiomyopathy, intensive care unit, sepsis, catecholamines, left ventricular dysfunction, case series

Address for Correspondence: Raj Sachde, Department of Cardiology, DY Patil Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Pimpri, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Email: rjsachde@gmail.com Mobile: +91 9624092892

ORCID: S.K. Malani - 0000-0003-2901-8549; C.Sridevi - 0000-0002-8192-416X; Raj Sachde - 0009-0009-5630-3143

Susheel K. Malani , C.Sridevi , Raj Sachde

DY Patil Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Pimpri, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Abstract

Objective: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) is an acute, transient left ventricular (LV) dysfunction that mimics acute coronary syndrome. Critically ill patients are particularly vulnerable due to heightened catecholamine response.

The aim of the study was to describe the clinical profile, electrocardiographic (ECG) and echocardiographic findings, and short-term outcomes of intensive care unit (ICU) patients diagnosed with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

Case presentation: This case series includes 5 ICU patients diagnosed with Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy between July 2025 and October 2025. Clinical presentation, ECG, biomarkers, echocardiographic findings and outcomes were analysed. Mean age was 50.6 years; 3 out of 5 cases were female. Common triggers were physical stressors like major trauma, missed abortion with severe sepsis, major surgery for active and metastasized carcinoma rectum, severe sepsis with ards, mechanical ventilatory support with bronchoscopy for recurrent lower respiratory tract infections. All had transient LV dysfunction. Apical ballooning was the most common pattern. Average recovery time was 2 weeks. In-hospital mortality was 1 out of 5 cases.

Conclusion: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy occurs in critically ill patients, often triggered by stress or sepsis, and carries favourable recovery potential with supportive management.

Key words: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, stress cardiomyopathy, intensive care unit, sepsis, catecholamines, left ventricular dysfunction, case series

Introduction

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC), also known as stress-induced cardiomyopathy or “broken-heart syndrome,” is a transient, reversible left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction that mimics acute coronary syndrome (ACS) but occurs in the absence of significant obstructive coronary artery disease. It was first described in Japan in the early 1990s and derives its name from the Japanese term “Takotsubo,” meaning an octopus trap, reflecting the typical apical ballooning of the left ventricle seen on imaging (1).

The precise pathophysiological mechanisms of TTC remain incompletely understood; however, catecholamine surge, coronary microvascular dysfunction, and myocardial stunning are widely recognized contributors.

Emotional or physical stressors often precipitate the syndrome, leading to transient regional wall-motion abnormalities extending beyond a single coronary vascular territory (2). Although classically reported in post-menopausal women following intense emotional stress, emerging data highlight that Takotsubo cardiomyopathy can also occur in critically ill patients, where triggers such as sepsis, respiratory failure, surgery, or exogenous catecholamine therapy play a significant role (1, 2).

The reported incidence of TTC among patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) ranges from 1% to 2% of all suspected ACS presentations (3). In this setting, its recognition is particularly challenging because hemodynamic instability, elevated cardiac biomarkers, and electrocardiographic (ECG) changes can closely mimic acute myocardial infarction or septic cardiomyopathy. Early echocardiography and coronary imaging are therefore crucial to establishing the diagnosis and guiding appropriate management (4).

Given these diagnostic challenges and the unique stressors inherent to critical illness, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in ICU patients represents a distinct and clinically relevant subset.

The present case series describes five such patients admitted to our ICU, outlining their clinical presentations, ECG and echocardiographic findings, possible triggers, and short-term outcomes. This series aims to emphasize the importance of considering stress cardiomyopathy as a differential diagnosis in critically ill patients presenting with acute LV dysfunction.

Methods

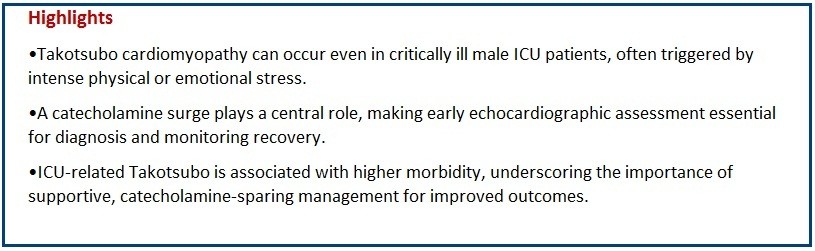

This is a retrospective observational cases treated in surgical and medical ICUs, at our hospital from July 2025 – October 2025. Cases were selected non-consecutively, based on symptom-based identification of ICU patients presenting with clinical features suggestive of Takotsubo syndrome, and inclusion required availability of complete clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic data.

All patients provided informed consent to procedures and treatment.

We collected demographics and comorbidities, type of trigger (emotional, sepsis, surgery, catecholamine therapy), ECG and echocardiographic findings, cardiac biomarkers (Troponin I, CK-MB, NT-proBNP), ICU course and complications and In-hospital and condition data at discharge.

Case Summires

Five patients (three females and two males) aged between 30 and 74 years presented with transient LV dysfunction consistent with stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy, each precipitated by a distinct physical or emotional trigger.

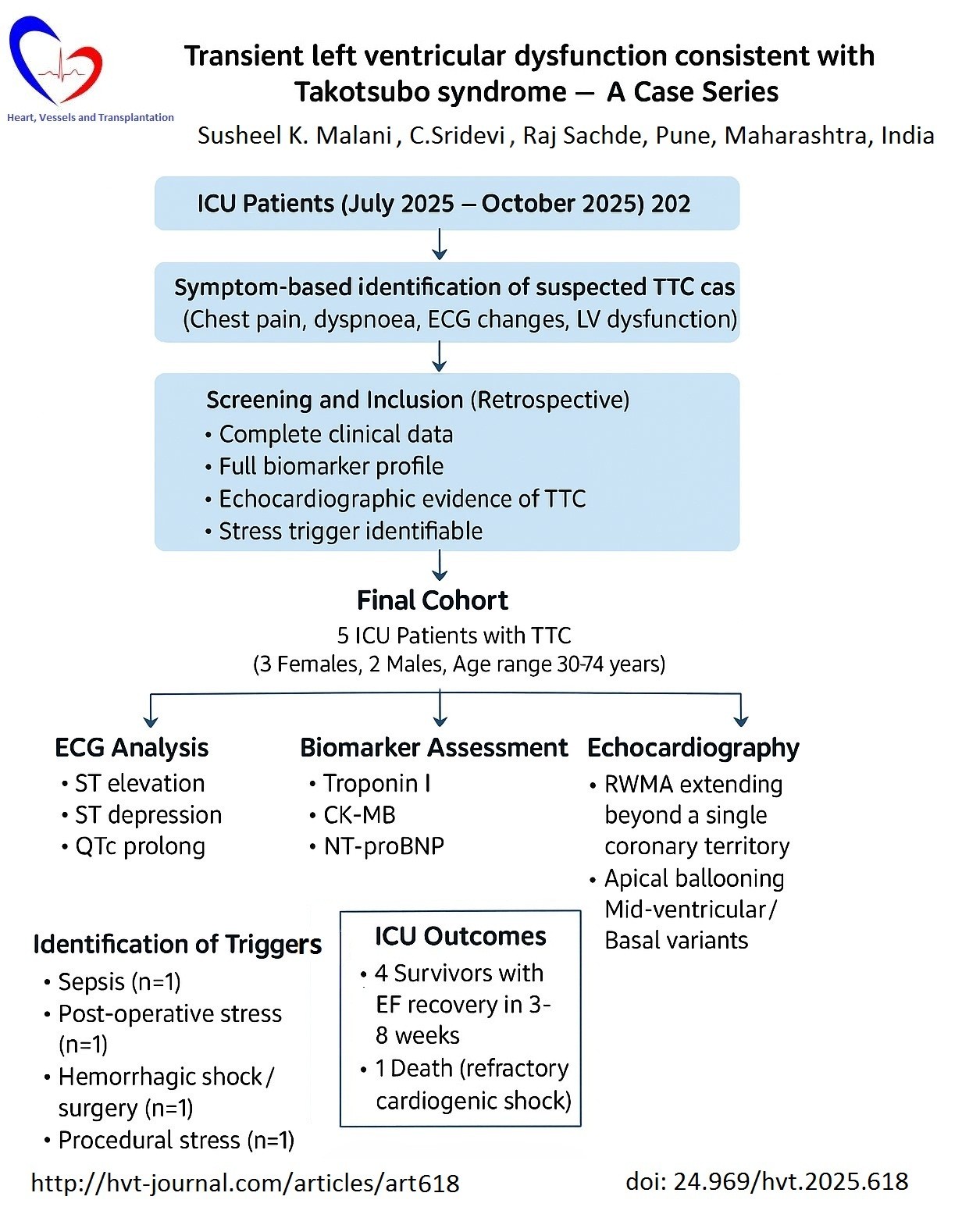

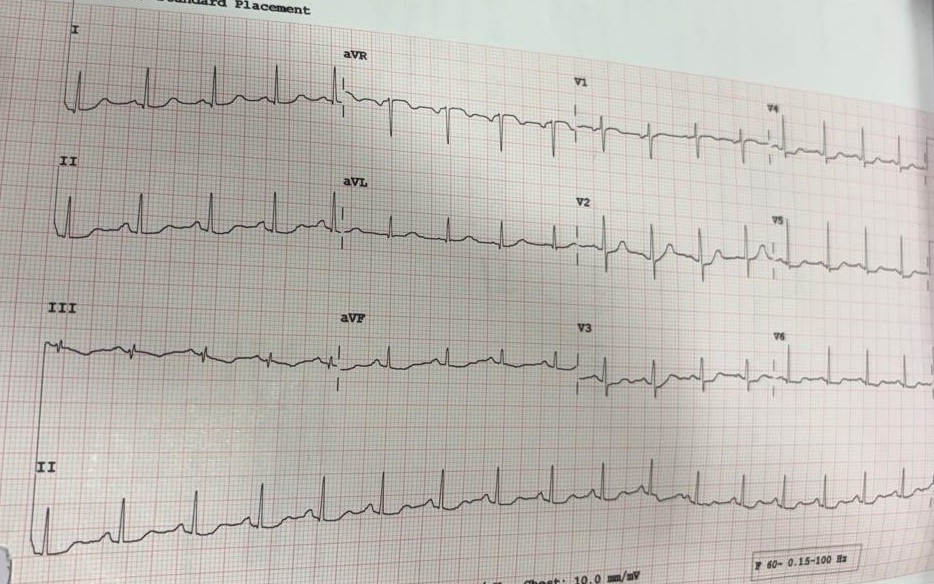

The first case, a 62-year-old female, developed chest discomfort during treatment for septic shock secondary to pneumonia. ECG showed ST elevation in leads V2–V5 with a prolonged QTc of 500 ms (Fig.1), and echocardiography revealed apical ballooning with an ejection fraction (EF) of 35–40%, which improved to 55% after three weeks.

Figure 1. Electrocardiogram shows ST elevation V2–V5, QTc 500 ms in case 1.

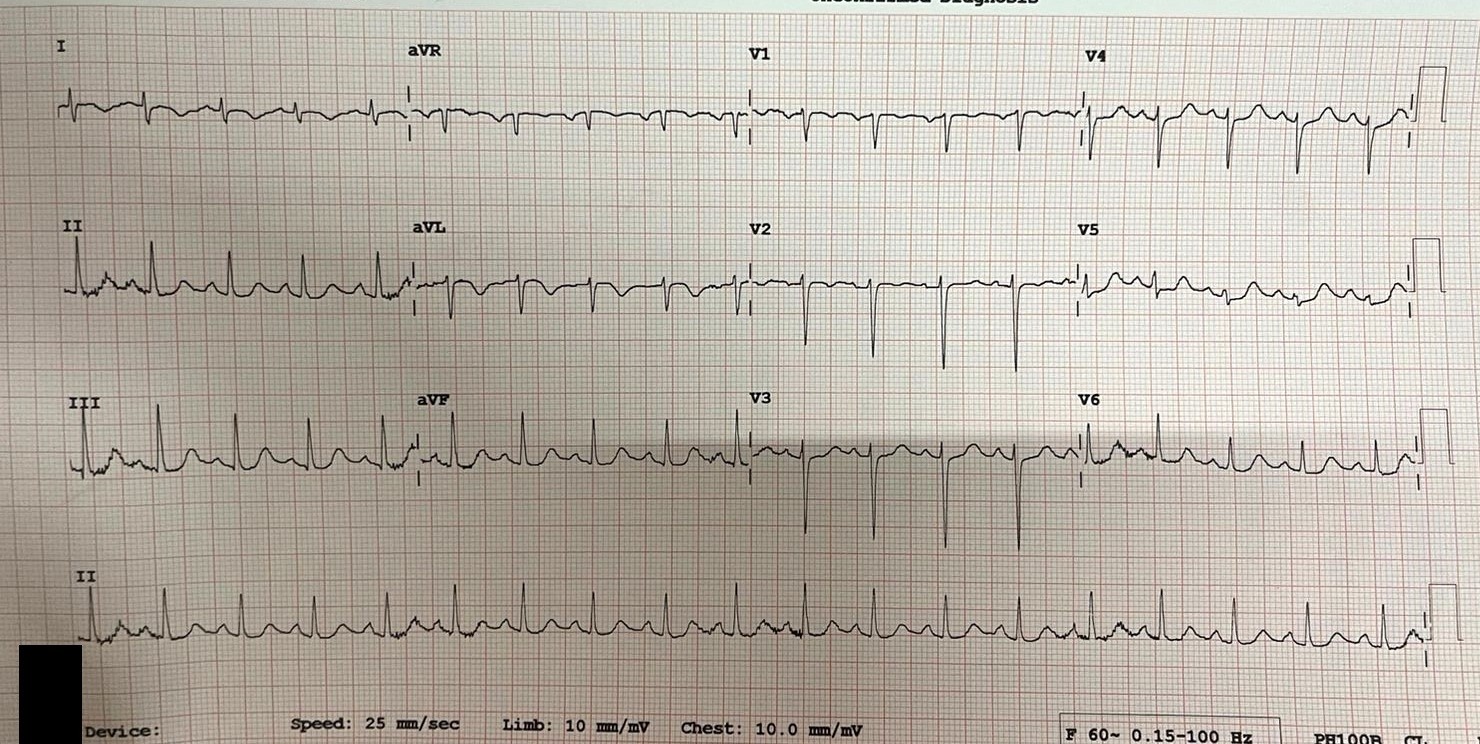

The second case involved a 74-year-old male with hypertension who developed acute decompensated heart failure on the second postoperative day following anterior resection for carcinoma rectum. ECG showed LV hypertrophy with strain but no acute ST-T changes (Fig.2). Echocardiography demonstrated global LV hypokinesia (apex > base, mid segments) with EF 30%, improving to 50–55% at six weeks.

Figure 2. Electrocardiogram shows normal axis, left ventricular hypertrophy with strain

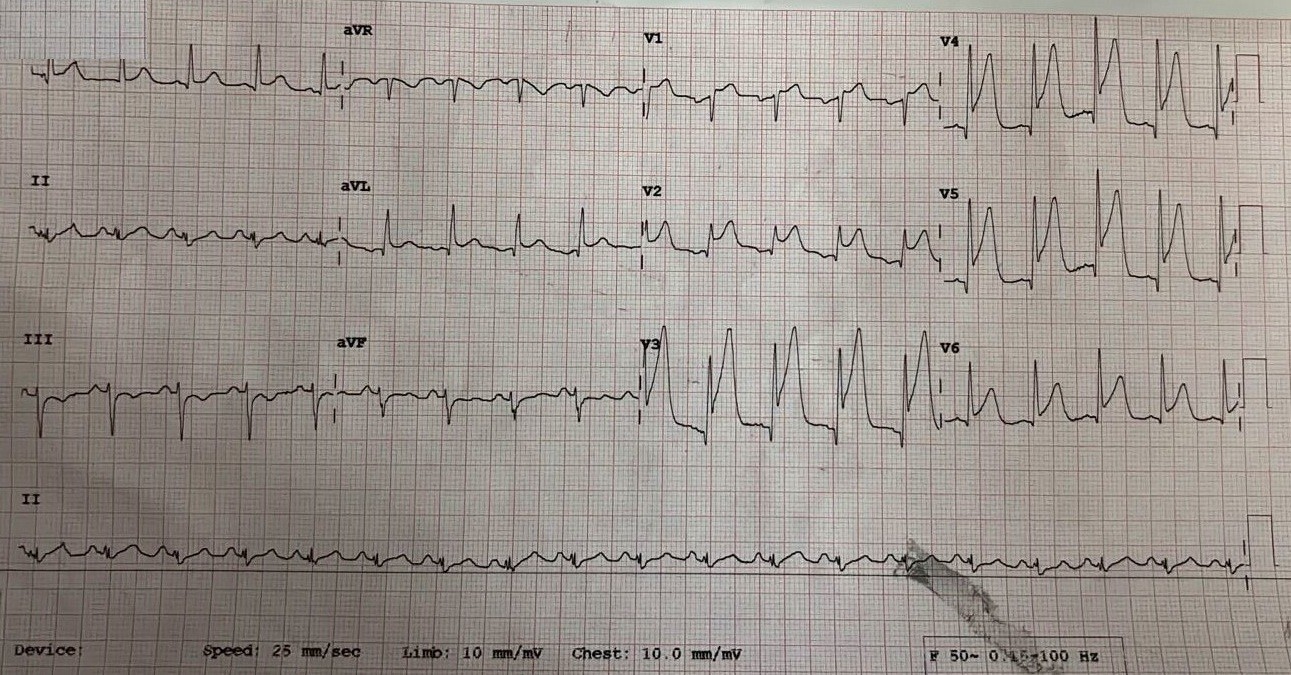

The third patient, a 30-year-old female, developed retrosternal chest pain and dyspnoea following surgery for ruptured ectopic pregnancy. ECG showed upsloping ST depression in leads V3–V6 (Fig.3), with echocardiography revealing severe LV dysfunction (EF 20–25%) and global hypokinesia predominantly involving basal and mid segments; EF recovered to 50–55% after five weeks.

Figure 3. Electrocardiogram shows normal axis, upsloping ST depression in V3-V6

The fourth case, a 35-year-old female undergoing bronchoscopy for lower respiratory tract infection with post-tubercular fibrosis, developed acute dyspnoea and palpitations immediately post-procedure. ECG showed right axis deviation with biphasic T waves in leads I and aVL (Fig. 4), and echocardiography revealed apical ballooning with preserved basal contractility (EF 35–40%), improving to 55% after three weeks.![]()

Figure 4. Electrocardiogram shows normal axis, ST elevation V1–V6

The fifth patient, a 52-year-old male involved in a high-impact road traffic accident, developed chest tightness 12 hours after admission. ECG showed ST elevation in V1–V6 (Fig. 5), and echocardiography demonstrated apical hypokinesia with preserved basal function (EF 35–40%). Despite aggressive inotropic support, the patient developed refractory cardiogenic shock and succumbed within 12 hours.

Figure 5. ST elevation V1–V6

In summary, all cases clinic and biomarkers and ICU course findings are mentioned in Table1. All cases demonstrated transient LV systolic dysfunction with characteristic regional wall motion abnormalities, modest elevation of cardiac biomarkers, and near-complete recovery of LV function in survivors within six to eight weeks follow up, consistent with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy triggered by diverse physical stressors. Coronary angiography was not done in any of the cases.

Three cases required vasopressors, 2 cases were treated additionally with diuretics and noninvasive ventilation, followed by improvement in EF, and were discharged on 3rd-7th week. One case developed cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest with 12 hours of admission.

|

Table 1. Summary of clinical, biomarker, ECG, echocardiographic and ICU course findings |

||||||||

|

Case |

Age (years) |

Sex |

ECG findings on admission |

Troponin I (pg/mL) |

CK-MB (ng/mL) |

NT-proBNP (pg/mL) |

Echocardiographic findings |

ICU Course / outcome |

|

1 |

62 |

Female |

ST elevation V2–V5, QTc 500 ms |

28 |

7.10 |

4800 |

Apical ballooning; EF 35–40%; improved to 55% at 3 weeks |

Required vasopressors; EF improved to 55% at 3 weeks |

|

2 |

74 |

Male |

LVH with strain; no acute ST-T changes |

81 |

4.27 |

17667 |

Global LV hypokinesia (apex > base); EF 30%; improved to 50–55% at 6 weeks |

Vasopressors, IV diuretics, NIV; discharged after 7 weeks |

|

3 |

30 |

Female |

Upsloping ST depression V3–V6 |

400 |

12.1 |

728 |

Global hypokinesia (basal/mid segments); EF 20–25%; improved to 50–55% at 5 weeks |

Required vasopressors; discharged after 6 weeks |

|

4 |

35 |

Female |

Right axis deviation; biphasic T waves I, aVL |

1013.1 |

6.7 |

3427 |

Apical ballooning; EF 35–40%; improved to 55% at 3 weeks |

Managed with NIV + IV diuretics; discharged after 4 weeks |

|

5 |

52 |

Male |

ST elevation V1–V6 |

420 |

7.9 |

6700 |

Apical hypokinesia; EF 35–40% |

Refractory cardiogenic shock; cardiac arrest within 12 hours |

|

CK-MB – creatine kinase MB fraction, ECG – electrocardiogram, EF – ejection fraction, ICU – intensive care unit, IV – intravenous, LV – left ventricular, LVH – left ventricular hypertrophy, NIV – noninvasive ventilation, NT-proBNP – N –terminal-pro-brain natriuretic peptide |

||||||||

Discussion

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC), or stress-induced cardiomyopathy, is increasingly recognized as an important cause of acute LV systolic dysfunction in critically ill patients. Although initially described in post-menopausal women following emotional stress, current evidence shows that physical stressors predominate in ICU presentations, accounting for nearly two-thirds of cases. Triggers such as sepsis, trauma, neurological injury, major surgery, and exogenous catecholamine administration can precipitate a catecholamine surge leading to transient myocardial stunning and characteristic regional wall-motion abnormalities extending beyond a single coronary vascular territory (1).

In the present case series of five ICU patients, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy occurred following varied stressors—including polytrauma, septic shock, and major procedures—highlighting the multifactorial nature of the syndrome in critical-care settings. While the apical ballooning variant remained predominant, mid-ventricular and basal variants were also observed, consistent with prior registry data (5, 6). Mild to moderate elevations of cardiac troponin and marked increases in natriuretic peptides were universal, reinforcing the diagnostic feature of biomarker–wall-motion mismatch, which helps differentiate TTC from acute myocardial infarction.

The male post-trauma patient who succumbed illustrates the potential for poor outcomes in physically triggered or ICU-associated Takotsubo syndrome. Several studies, including the InterTAK Registry, have shown that male sex, physical stress, and shock at presentation are independent predictors of adverse prognosis (7). In contrast, emotionally triggered cases tend to have benign courses with complete recovery of LV function within weeks.

The higher mortality in critical-care TTC likely reflects concomitant multiorgan dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and the adverse hemodynamic impact of vasopressors and inotropes, which may exacerbate catecholamine-mediated myocardial injury (8).

Echocardiography remains the cornerstone of diagnosis and monitoring. It allows rapid recognition of characteristic ballooning patterns, assessment of LV outflow-tract obstruction, and evaluation for LV thrombus formation. In resource-limited ICU environments, bedside echocardiography and serial imaging are invaluable for differentiating TTC from sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy or ischemic injury. Although coronary angiography is essential for excluding obstructive coronary artery disease, it may not always be feasible in hemodynamically unstable patients. In our series, selective angiography confirmed normal epicardial coronaries whenever performed.

Management in the ICU is largely supportive: meticulous hemodynamic optimization, diuretics for congestion, and judicious use of β-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors after stabilization. Excessive catecholamine use should be avoided, and mechanical circulatory support (intra-aortic balloon pump, IABP and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ECMO) may be lifesaving in refractory cases (9).

Most survivors in this series demonstrated complete recovery of LV function within four to eight weeks, reaffirming the reversible nature of the syndrome when early recognition and conservative management are achieved.

Conclusion

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the ICU represents a distinct clinical entity characterized by non-ischemic, stress-related, reversible myocardial dysfunction. Recognition of its varied presentations—especially in male or physically stressed patients—is essential to prevent misdiagnosis as ACS and to avoid unnecessary invasive interventions.

Our experience emphasizes that prompt echocardiographic evaluation, limitation of catecholamine exposure, and supportive care can substantially improve outcomes, although mortality remains significant when TTC complicates multiorgan failure. Coronary angiography is the gold standard to establish a definitive diagnosis of Takotsubo syndrome. The primary purpose is to exclude acute myocardial infarction with obstructive coronary artery disease, which can present identically to Takotsubo syndrome as major limitations of the manuscript.

Take home messages

•Takotsubo cardiomyopathy can occur in men as well as women and in critically ill ICU patients following intense physical or emotional stress.

•Catecholamine surge—endogenous or iatrogenic—is central to its pathophysiology.

•Echocardiography is crucial for early recognition, differentiation from acute coronary syndrome, and follow-up of recovery.

•ICU-associated Takotsubo carries higher morbidity and mortality compared to emotionally triggered cases.

•Supportive, catecholamine-sparing management and early hemodynamic optimization are key to survival and functional recovery.

Ethics: All patients included in the study provided written informed consent for procedure and treatment

Peer-review: External and internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: S.K.M., C.S. , and R.S. equally contributed to management of patients and preparation of manuscript and fulfilled all authorship criteria

Acknowledgements: None to declare

Funding: This work was supported by DY Patil Medical College Hospital and Research Centre itself and received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not for profit sectors.

Statement on A.I.-assisted technologies use: Authors declared they did not use AI-assisted technologies in preparation of this manuscript

Data and material availability: Contact authors. Any share should be in frame of fair use with acknowledgement of source and/or collaboration.

References

| 1.Ahmad SA, Brito D, Khalid N. Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy.(Updated 2023 May 22). StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024. | ||||

| 2.Cacciapuoti F, Capone V, Crispo S, Gottilla R, La Rocca F, Esposito M, et al. Beyond the broken heart: Unusual triggers of stress cardiomyopathy-A narrative review. Heart Mind 2025; 9: 215-23. https://doi.org/10.4103/hm.HM-D-24-00114 |

||||

| 3.Poruban T, Studencan M, Kirsch P, Novotny R. Incidence of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a single center retrospective analysis. Egypt Heart J 2024; 76: 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43044-024-00542-x PMid:39186244 PMCid:PMC11347531 |

||||

| 4.Aissaoui N, Boissier F, Chew M, Singer M, Vignon P. Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2025; 46: 3339-53. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf340 PMid:40439150 |

||||

| 5.Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, Napp LC, Bataiosu DR, Jaguszewski M, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 929-38. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1406761 PMid:26332547 |

||||

| 6.Grapsa J, Fuster V. JACC: Case Reports: A Year of transformation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021; 77: 3226-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.05.029 PMid:34167647 |

||||

| 7.Kato K, Di Vece D, Kitagawa M, Yamamoto K, Miyakoda K, Aoki S, et al Clinical characteristics and outcomes in Takotsubo syndrome-Review of insights from the InterTAK Registry. J Cardiol 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2025.01.009 PMid:39892867 |

||||

| 8.Jentzer JC, Hollenberg SM. Vasopressor and inotrope therapy in cardiac critical care. J Intensive Care Med 2021; 36: 843-56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066620917630 PMid:32281470 |

||||

| 9.Santoro F, D'Apollo R, Brunetti ND. Increased right amygdala activity during the hyper-acute phase of Takotsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J 2023; 44: 2260. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad302 https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad302 PMid:37204920 |

||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER