Impact of frailty on clinical outcomes in elderly patients after transcatheter aortic valve replacement

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Impact of frailty on clinical outcomes in elderly patients after transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2025.620

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 17/12/2025

- Received: 13/11/2025

- Revised: 04/12/2025

- Accepted: 05/12/2025

- Views: 699

- Downloads: 337

- Keywords: Frailty, TAVR, elderly, aortic stenosis, outcomes

Address for Correspondence: Nguyen Quang Minh, 201B Nguyen Chi Thanh, District 5, Ho Chi Minh City, 700000 Vietnam

Email: nqm2406@gmail.com Phone: +84 334153053

ORCID: Nguyen Quang Minh -0009-0000-7391-8793

Nguyen Quang Minh1*, Kieu Ngoc Dung1, Nguyen Tri Thuc1, Pham Hoa Binh2, Vo Thanh Nhan2

1Cho Ray Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

2Department of Geriatrics, University of Medicine and Pharmacy HCMC, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Abstract

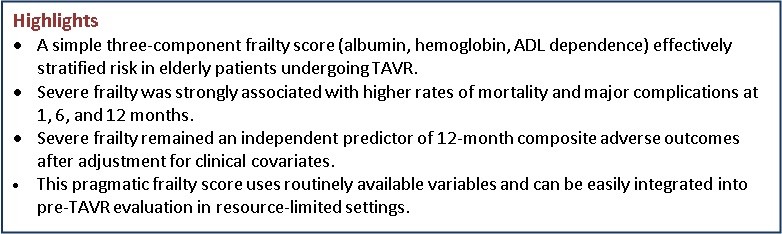

Objective: Frailty is increasingly recognized as a key determinant of outcomes in elderly patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). However, the optimal approach for frailty assessment in routine practice remains uncertain.

Methods: We performed a retrospective single-center study including elderly patients (≥60 years, consistent with WHO definitions for developing countries) with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis undergoing TAVR. Frailty status was assessed using three routinely available clinical indicators: hypoalbuminemia, anemia, and dependence in activities of daily living (ADL). Frailty severity was defined by the number of abnormal indicators (0–3). The primary endpoint was a composite of procedural failure, major complications, and all-cause mortality at 1, 6, and 12 months.

Results: Seventy-three patients were included. Composite adverse outcomes occurred in 34.3%, 37.0%, and 38.4% at 1, 6, and 12 months. Severe frailty (three indicators) was associated with significantly higher event rates. Severe frailty remained an independent predictor of 12-month composite outcomes (OR 5.44; 95% CI 1.68–7.52).

Conclusion: A simple three-component frailty score based on albumin, hemoglobin, and ADL dependence effectively identifies high-risk elderly TAVR candidates. Incorporating this frailty assessment into preprocedural evaluation may support better risk stratification and clinical decision-making.

Key words: Frailty, TAVR, elderly, aortic stenosis, outcomes

List of abbreviations

TAVR - Transcatheter aortic valve replacement

ADL - Activities of daily living

AS -Aortic stenosis

SAVR - Surgical aortic valve replacement

AKI - Acute kidney injury

IRB - Institutional review board

VARC-2 - Valve Academic Research Consortium-2

STS-PROM - Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular heart disease among older adults and is frequently accompanied by multiple comorbidities and age-related physiological decline (1). Once symptoms develop, prognosis without intervention is poor, with nearly half of patients dying within two years (2). Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) remains the standard treatment; however, many elderly individuals are suboptimal candidates because of frailty, limited reserve, or high procedural risk.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has become an established alternative for patients at intermediate or high surgical risk, offering comparable or superior survival and functional improvement in selected populations (3). Despite these advantages, outcomes following TAVR remain heterogeneous, and patient-specific factors—particularly frailty—play a major role in predicting procedural success and long-term prognosis (3).

Frailty represents a multidimensional syndrome characterized by decreased physiological reserve and increased vulnerability to stressors (4). Previous research consistently demonstrates its strong association with mortality, complications, functional decline, and rehospitalization after TAVR (5). However, despite its clinical relevance, there is no consensus on the optimal frailty assessment tool for TAVR candidates. Many existing measures are time-consuming, require specialized geriatric evaluation, or rely on subjective domains, limiting their applicability in routine practice.

To address this gap, we evaluated a practical frailty assessment based on three routinely available clinical indicators—serum albumin, hemoglobin concentration, and dependence in activities of daily living (ADL). We hypothesized that this simplified multidomain score would effectively risk-stratify elderly TAVR candidates and identify individuals at increased risk of adverse outcomes. In developing countries, including Vietnam, older adults are commonly defined as individuals aged 60 years and above, according to WHO and national public health classifications. Therefore, our study population—comprising patients aged ≥60 years—corresponds to the locally accepted definition of the elderly. Differences in demographic structure and earlier onset of cardiovascular disease in Asian populations may also result in younger TAVR cohorts compared with Western countries.

The aim of this study was to assess the association between this pragmatic frailty score and clinical outcomes at 1, 6, and 12 months following TAVR.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of elderly patients with symptomatic severe AS who underwent TAVR at a single tertiary cardiovascular center between January 2017 and May 2022. Severe AS was confirmed by transthoracic echocardiography based on established guideline criteria. Eligible patients were those deemed appropriate candidates for TAVR by a multidisciplinary heart team. Patients with incomplete clinical records or missing follow-up data were excluded. All exclusions occurred before final cohort assembly; therefore, no imputation was needed. The design, conduct, and reporting of this observational study followed the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines. All consecutive eligible patients undergoing TAVR during the study period were included. Patients who developed periprocedural complications or required permanent pacemaker implantation after TAVR were not excluded and were captured as outcome events.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2024 and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (Approval No. 536/HDDD-DHYD, November 9, 2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Baseline variables

Baseline demographic characteristics (age, sex, body mass index); comorbidities (Hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, prior stroke/transient ischemic attack, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, multimorbidity (≥3 diseases)); laboratory parameters (serum hemoglobin, albumin and glomerular filtration rate); echocardiographic findings (presence of bicuspid aortic valve, aortic valve area, peak and mean gradients, tricuspid regurgitation); and procedural details (valve type, valve size, femoral access) were obtained from institutional electronic medical records. In-hospital events and complications were prospectively documented. Patients with incomplete clinical records or missing follow-up information at any time point were excluded during the initial screening process. As a result, all patients included in the final analysis had complete follow-up data at 1, 6, and 12 months, with no losses to follow-up after enrollment.

Frailty score

Frailty status was determined using three objective clinical markers. The cutoffs for each frailty indicator were selected based on prior literature evaluating prognostic markers in TAVR populations. A serum albumin level <35 g/L has been widely used in previous studies as a marker of malnutrition and systemic inflammation associated with increased post-TAVR risk. Similarly, anemia defined as hemoglobin <13 g/dL in men and <12 g/dL in women follows WHO criteria and has been adopted in large TAVR cohorts investigating the impact of anemia on clinical outcomes. Functional dependence in at least one Katz ADL domain has been validated as a predictor of mortality and postoperative recovery in TAVR studies. Therefore, these thresholds reflect evidence-based definitions used in prior clinical research (5).

Each abnormal indicator was assigned one point, resulting in a frailty score ranging from 0 to 3. Patients were categorized into four groups: Non-frail: 0 abnormal indicators (F0); Mild frailty: 1 abnormal indicator (F1); Moderate frailty: 2 abnormal indicators (F2); Severe frailty: 3 abnormal indicators (F3).

TAVR procedure

All procedures were performed in a hybrid catheterization laboratory using standard transfemoral or alternative access according to operator discretion. Self-expanding (Evolut R) or balloon-expandable (Portico) prostheses were implanted under fluoroscopic and echocardiographic guidance. Periprocedural management and post-procedural care followed contemporary guideline-based protocols.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was a composite clinical endpoint that included: procedural failure, all-cause mortality, major vascular complications, major bleeding, acute kidney injury (AKI), stroke, permanent pacemaker implantation (PPI). All components were defined according to Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 (VARC-2) criteria (6).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.0.Continuous variables are expressed as mean (standard deviation, (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate for normally and abnormally distributed variables. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages and compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

Multivariable analysis was primarily conducted for the 12-month composite endpoint to avoid overfitting; 1- and 6-month analyses are presented descriptively. Variables with a p-value <0.10 in univariate analyses or those considered clinically relevant were included in the adjusted models. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 73 elderly patients with symptomatic severe AS who underwent TAVR were included. The median age was 69 years (IQR 62–76), and 43.8% were female. Common comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and coronary artery disease, bicuspid aortic valve was found in 23.3%, moderate-severe tricuspid regurgitation in 11%, 97.3% of patients were implanted the Evolute valve and 2.7% - Portico valve, almost all patients underwent TAVR using femoral access. Baseline clinical and procedural characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Baseline clinical, laboratory, echocardiographic, and procedural characteristics of patients undergoing TAVR (n = 73) |

|

|---|---|

|

Variables |

Value |

|

Demographics |

|

|

Age, years |

69 (62–76) |

|

Female sex, n (%) |

32 (43.8) |

|

BMI, kg/m² |

22.42 (3.20) |

|

Underweight (BMI <18.5), n (%) |

6 (8.2) |

|

Comorbidities |

|

|

Hypertension, n (%) |

50 (68.5) |

|

Dyslipidemia, n (%) |

43 (58.9) |

|

Diabetes mellitus, n (%) |

16 (21.9) |

|

Coronary artery disease, n (%) |

18 (24.7) |

|

Chronic kidney disease, n (%) |

7 (9.6) |

|

Prior stroke/TIA, n (%) |

4 (5.5) |

|

Atrial fibrillation, n (%) |

7 (9.6) |

|

COPD, n (%) |

6 (8.2) |

|

Multimorbidity (≥3 diseases), n (%) |

32 (43.8) |

|

Laboratory parameters |

|

|

Hemoglobin, g/dL |

12.48 (1.54) |

|

Albumin, g/L |

36.20 (32.60–39.47) |

|

Continues on page XXX |

|

|

Table 1. Baseline clinical, laboratory, echocardiographic, and procedural characteristics of patients undergoing TAVR (n = 73) Continues from page XXX |

|

|---|---|

|

Variables |

Value |

|

GFR, mL/min/1.73 m² |

53.10 (16.47) |

|

Echocardiographic findings |

|

|

LVEF, % |

57.71 (14.89) |

|

Aortic valve area, cm² |

0.62 (0.18) |

|

Peak velocity, m/s |

4.93 (0.81) |

|

Mean gradient, mmHg |

63.96 (22.49) |

|

Bicuspid aortic valve, n (%) |

17 (23.3) |

|

Moderate–severe TR, n (%) |

8 (11.0) |

|

Procedural details |

|

|

Valve type: Evolut R, n (%) |

71 (97.3) |

|

Valve type: Portico, n (%) |

2 (2.7) |

|

Femoral access, n (%) |

70 (95.9) |

|

Valve size, mm |

28.63 (3.14) |

|

Data are presented as number (%), median (IQR) and mean (SD) BMI – body mass index, COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, GFR – glomerular filtration rate, IQR –interquartile range, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, TAVR – transcatheter aortic valve replacement, TIA – transient ischemic attack, TR – tricuspid regurgitation |

|

Frailty Distribution

Based on the three-component frailty score, 19 patients (26.0%) were non-frail, 25 (34.2%) mildly frail, 16 (21.9%) moderately frail, and 13 (17.8%) severely frail. The distribution of frailty categories is shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2. Frailty status |

||

|

Frailty group |

n |

% |

|

Non-frail |

19 |

26.0 |

|

Mild frailty (1 indicator) |

25 |

34.2 |

|

Moderate frailty (2 indicators) |

16 |

21.9 |

|

Severe frailty (3 indicators) |

13 |

17.8 |

Clinical Outcomes

As can be seen from Table 3, overall, clinical event rates increased progressively over time. At 12 months, 38.4% of patients experienced at least one adverse event, with AKI (17.8%), PPI 11.0%), and major bleeding (9.6%) being the most frequent complications. Stroke occurred in 4.1% of patients, while mortality rose from 2.7% at 1 month to 10.9% at 12 months. The distribution of outcomes highlights the substantial burden of early and late complications following TAVR in this population.

All-cause mortality also showed a progressive rise over time, with 2 deaths (2.74%) at 1 month, 4 deaths (5.48%) at 6 months, and 8 deaths (10.96%) at 12 months.

The mean length of hospital stay was 10.1 ± 3.35 days (range 4–18). Conversion to ICU occurred in 1 patient (1.37%). Procedural failure was observed in 4 patients (5.48%) according to VARC-2 definitions.

Predictors of adverse outcomes

Univariate analysis

In the univariate logistic regression analysis, several baseline clinical variables were associated with the 12-month composite outcome. Severe frailty, underweight status, low albumin level, anemia, and history of syncope demonstrated significant associations with adverse events. Other variables such as diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, and reduced LVEF showed weaker or nonsignificant relationships.

|

Table 3. Component clinical outcomes after TAVR |

||

|

Outcome |

n |

% |

|

Acute kidney injury |

13 |

17.81 |

|

Permanent pacemaker implantation |

8 |

10.96 |

|

Major bleeding |

7 |

9.59 |

|

Procedural failure |

4 |

5.48 |

|

Stroke |

3 |

4.11 |

|

Major vascular complications |

3 |

4.11 |

|

All-cause mortality |

|

|

|

– 1 month |

2 |

2.74 |

|

– 6 months |

4 |

5.48 |

|

– 12 months |

8 |

10.96 |

|

Composite adverse outcome |

|

|

|

– 1 month |

25 |

34.25 |

|

– 6 months |

27 |

36.99 |

|

– 12 months |

28 |

38.36 |

All variables included in the univariate analysis, along with their OR, 95% CI, and p values, are presented in Table 4.

|

Table 4. Univariate analysis of predictors of composite clinical outcomes of patients after TAVR |

|||

|

Variable |

OR |

95% CI |

p |

|

Age group |

|||

|

– 60–69 years (reference) |

– |

– |

– |

|

– 70–79 years |

1.32 |

0.43–4.02 |

0.625 |

|

– ≥ 80 years |

2.10 |

0.65–6.74 |

0.214 |

|

Male sex |

0.63 |

0.25–1.59 |

0.323 |

|

Underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m²) |

6.55 |

1.20–32.01 |

0.056 |

|

BSA |

0.79 |

0.05–3.55 |

0.870 |

|

Syncope |

5.74 |

1.44–8.80 |

0.013 |

|

NYHA class |

|||

|

– Class II (reference) |

– |

– |

– |

|

– Class III |

0.44 |

0.15–1.35 |

0.152 |

|

– Class IV |

1.92 |

0.16–2.56 |

0.603 |

|

Dyslipidemia |

2.53 |

0.96–6.66 |

0.063 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

2.29 |

0.73–7.16 |

0.154 |

|

Previous stroke |

3.68 |

0.36–7.13 |

0.051 |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

3.14 |

0.93–7.50 |

0.059 |

|

Coronary artery disease |

1.20 |

0.45–3.48 |

0.737 |

|

Chronic kidney disease |

3.19 |

0.58–7.64 |

0.184 |

|

COPD |

1.16 |

0.22–6.17 |

0.861 |

|

Multimorbidity |

2.01 |

0.79–5.14 |

0.145 |

|

STS-PROM score |

|||

|

– <3% (reference) |

– |

– |

– |

|

– 3–8% |

3.22 |

1.10–9.40 |

0.001 |

|

– >8% |

8.75 |

2.01–33.45 |

<0.001 |

|

Glomerular filtration rate |

0.96 |

0.93–0.99 |

0.030 |

|

Continues on page XXX |

|||

|

Table 4. Univariate analysis of predictors of composite clinical outcomes of patients after TAVR Continues from page XXX |

|||

|

Variable |

OR |

95% CI |

p |

|

Pre-TAVR LVEF |

0.99 |

0.97–1.03 |

0.834 |

|

Aortic annulus diameter |

1.06 |

0.98–1.15 |

0.127 |

|

Maximum transvalvular velocity |

1.61 |

0.89–2.93 |

0.117 |

|

Mean aortic gradient |

1.02 |

0.99–1.04 |

0.164 |

|

Bicuspid valve |

1.03 |

0.35–3.04 |

0.964 |

|

Moderate–severe TR |

3.96 |

0.74–7.14 |

0.098 |

|

Femoral access |

0.42 |

0.04–4.86 |

0.488 |

|

Balloon predilation |

8.17 |

1.80–37.12 |

0.007 |

|

Hospital stay ≥7 days |

3.35 |

1.27–8.79 |

0.014 |

|

Blood loss volume |

1.01 |

1.00–1.01 |

0.010 |

|

Frailty score |

|

|

|

|

– F0 (reference) |

– |

– |

– |

|

– F1 |

4.92 |

1.14–8.23 |

0.033 |

|

– F2 |

5.33 |

1.10–9.77 |

0.037 |

|

– F3 |

9.33 |

2.50–35.02 |

0.001 |

|

BMI – body mass index, BSA - body surface area, CI – confidence interval, COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, OR – odds ratio, TAVR – transcatheter aortic valve replacement, TR – tricuspid regurgitation |

|||

Multivariable analysis

Variables with p < 0.10 in the univariate analysis or strong clinical relevance were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model.

In the final adjusted model, severe frailty remained an independent predictor of the 12-month composite outcome (OR 5.44; 95% CI 1.68–7.52; p = 0.024). Other variables such as syncope and underweight status demonstrated weaker associations, while presence of tricuspid regurgitation and STS-PROM score 4-8% showed association, but all did not remain significant after adjustment.

The full multivariable model with OR, 95% CI, and p values is presented in Table 5.

|

Table 5. Multivariable logistic regression for 12-month composite outcome after TAVR |

|||

|

Variables |

OR |

95% CI |

p |

|

Underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m²) |

2.99 |

1.22–3.93 |

0.037 |

|

Syncope |

2.94 |

1.28–3.17 |

0.033 |

|

STS-PROM score |

|

|

|

|

– <3% (reference) |

– |

– |

– |

|

– 3–8% |

5.53 |

0.48–8.27 |

0.172 |

|

– >8% |

6.72 |

1.01–7.20 |

0.048 |

|

Glomerular filtration rate |

1.01 |

0.95–1.08 |

0.667 |

|

Moderate–severe tricuspid regurgitation |

5.06 |

1.45–9.11 |

0.033 |

|

Frailty score |

|

|

|

|

– F0 (reference) |

– |

– |

– |

|

– F1 |

1.28 |

0.10–5.72 |

0.847 |

|

– F2 |

2.34 |

0.13–4.86 |

0.562 |

|

– F3 |

5.44 |

1.68–7.52 |

0.024 |

For the 1-month and 6-month composite outcomes, univariate analyses demonstrated similar patterns to those observed at 12 months, with severe frailty, underweight status, and syncope showing consistent associations with increased risk.

In multivariable models at these earlier time points, severe frailty likewise remained an independent predictor of adverse outcomes, although effect estimates were less stable due to the smaller number of events (Table 6). Therefore, the primary multivariable model presented in Table 5 focuses on the 12-month outcomes, which reflect the most clinically meaningful endpoint and offer greater statistical robustness.

|

Table 6. Association between frailty and adverse outcomes after TAVR |

||

|

Outcome time point |

OR (95% CI) |

p |

|

1 month |

3.19 (1.61–10.85) |

0.030 |

|

6 months |

4.16 (1.32–8.96) |

0.036 |

|

12 months |

5.44 (1.68–7.52) |

0.024 |

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort of elderly patients undergoing TAVR, we found that a simple three-component frailty score—based on serum albumin, hemoglobin levels, and dependence in ADLs—was strongly associated with adverse outcomes at 1, 6, and 12 months. Patients classified as severely frail demonstrated consistently worse prognosis across all time points, even after adjustment for conventional clinical predictors. We elected to present the multivariable model for 12-month outcomes only, as this endpoint had the highest number of events and therefore provided the most statistically stable estimates. Analyses at 1 and 6 months showed similar trends but were not presented in full due to limited event numbers. These findings highlight the prognostic importance of frailty in contemporary TAVR practice and underscore the value of a pragmatic frailty assessment tool that can be readily implemented in routine care.

Our results align with prior studies demonstrating that frailty is a key determinant of early and late outcomes following TAVR. Puls et al. (2) reported that impaired Katz ADL scores were significantly associated with short- and long-term mortality after TAVR, reinforcing the importance of functional status as a core component of frailty evaluation. Similarly, Forcillo and colleagues (7) identified ADL dependence as a powerful predictor of adverse events among high- and extreme-risk TAVR patients. These findings support the integration of functional measures—such as ADL assessments—into preprocedural decision-making.

Beyond functional decline, our study also confirms the prognostic relevance of biological frailty markers. Low serum albumin, a surrogate of malnutrition and systemic inflammation, has repeatedly been linked to increased mortality, bleeding, and rehospitalization after TAVR (5, 8). Likewise, anemia is prevalent in up to half of TAVR candidates and is associated with adverse long-term outcomes (5). Kiani et al. (5), in an analysis of over 36,000 TAVR cases, demonstrated that preprocedural anemia independently increased one-year mortality. The combined use of these two objective biomarkers provides a simple yet powerful reflection of physiological reserve.

Compared with more complex frailty indices—such as the Fried phenotype (4), the Rockwood Frailty Index, or the Essential Frailty Toolset (EFT) (5)—our score offers several practical advantages. It relies solely on routinely available laboratory and functional data, is easily reproducible, and does not require specialized geriatric evaluation or additional testing. This practicality is particularly valuable in busy structural heart programs and resource-limited settings. Importantly, the clear gradient observed across frailty categories in our cohort suggests that this simple model captures meaningful biological and functional vulnerability.

The implications for clinical practice are notable. Incorporating frailty assessment into preprocedural evaluations may improve risk stratification, guide discussions with patients and families, and help clinicians anticipate perioperative needs. Frail patients may benefit from targeted optimization strategies—including nutritional support, anemia correction, and structured rehabilitation—prior to and after TAVR. Future studies should evaluate whether modifying these frailty components can translate into improved outcomes.

The median age of our cohort (69 years) is younger than that reported in Western TAVR registries. This reflects regional epidemiology, earlier disease manifestation, and referral patterns in developing countries. In Vietnam, as well as other low- and middle-income countries, the threshold for defining older adults is ≥60 years based on WHO criteria, which aligns with the age distribution of our study population. Nevertheless, this difference should be considered when generalizing our findings to older Western cohorts.

It is important to acknowledge that both low serum albumin and anemia may be influenced by comorbid conditions that independently worsen prognosis after TAVR, such as chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, malignancy, chronic inflammation, or advanced heart failure. Consequently, the association between our three-component frailty score and adverse outcomes may in part reflect the underlying burden of comorbid disease rather than ‘frailty’ in a narrow sense.

To mitigate this potential confounding, we included several major comorbidities and global risk indices (including chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, previous stroke, atrial fibrillation, multimorbidity, and the STS-PROM score) in the univariate analyses, and incorporated clinically relevant variables into the multivariable model. Even after this adjustment, severe frailty remained an independent predictor of 12-month adverse outcomes. This suggests that our frailty score captures a broader construct of biological vulnerability that integrates nutritional, hematologic, functional, and comorbidity-related domains, which may actually be desirable in routine risk stratification. Nevertheless, residual confounding by unmeasured or incompletely characterized comorbidities cannot be excluded and should be considered when interpreting our findings.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the retrospective single-center design may limit generalizability. Second, the sample size was relatively modest, reducing statistical power for less frequent outcomes. Third, while our frailty score is practical and effective, it does not account for other validated frailty domains such as gait speed or grip strength. Lastly, follow-up was limited to 12 months; longer-term consequences of frailty remain to be established.

Conclusion

In this cohort of elderly patients undergoing TAVR, frailty assessed using a simple three-component score—incorporating serum albumin, hemoglobin, and ADL dependence—was a strong independent predictor of adverse outcomes at 1, 6, and 12 months. Patients with severe frailty consistently experienced the highest risk profiles. Because this score relies entirely on parameters readily available in routine clinical practice, it offers a practical and easily implementable approach for risk stratification. Integrating this assessment into preprocedural evaluation may enhance clinical decision-making, optimize perioperative management, and support shared discussions between clinicians, patients, and families. Further prospective studies are needed to validate this approach in larger and more diverse populations and to determine whether targeted interventions addressing frailty can improve post-TAVR outcomes. Given the retrospective single-center design and modest sample size, these findings should be considered hypothesis-generating and warrant confirmation in larger multicenter cohorts.

Ethics: The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2024 and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (Approval No. 536/HDDD-DHYD, November 9, 2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Peer-review: External and internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: N.Q.M., K.N.D., N.T.T., P.H.B., and V.T.N. equally contributed to the study, preparation of manuscript and fulfilled all authorship criteria

Acknowledgements and Funding: None to declare. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Statement on A.I.-assisted technologies use: Artificial intelligence (A.I.) tools were used only for minor language editing and formatting. No part of the scientific content, analysis or interpretation was generated by A.I.

Data and material availability: Contact authors. Any share should be in frame of fair use with acknowledgement of source and/or collaboration

References

| 1. Iung B, Vahanian A. Degenerative calcific aortic stenosis: a natural history. Heart 2012; 98(Suppl 4): iv7-iv13. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302395 https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302395 PMid:23143128 |

||||

| 2. Puls M, Sobisiak B, Bleckmann A, Jacobshagen C, Danner BC, Hünlich M, et al. Impact of frailty on short- and long-term morbidity and mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: risk assessment by Katz Index of activities of daily living. EuroIntervention 2014; 10: 609-19. doi:10.4244/EIJY14M08_03 https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJY14M08_03 PMid:25136880 |

||||

| 3. Cockburn J, Singh MS, Rafi NH, Dooley M, Hutchinson N, Hill A, et al. Poor mobility predicts adverse outcome better than other frailty indices in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2015; 86: 1271-7. doi:10.1002/ccd.25991 https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.25991 PMid:26119601 |

||||

| 4. Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56: M146-56. doi:10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 PMid:11253156 |

||||

| 5. Kiani S, Stebbins A, Thourani VH, Forcillo J, Vemulapalli S, Kosinski AS, et al. The effect and relationship of frailty indices on survival after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2020; 13: 219-31. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2019.10.054 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2019.10.054 PMid:31973799 |

||||

| 6. Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. Eur Heart J 2012;33: 2403-18. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs255 https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs255 PMid:23026477 |

||||

| 7. Forcillo J, Condado JF, Ko YA, Yuan M, Binongo JN, Ndubisi NM, et al. Assessment of commonly used frailty markers for high- and extreme-risk patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2017; 104: 1939-46. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.05.067 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.05.067 PMid:28942076 |

||||

| 8. Hebeler KR, Baumgarten H, Squiers JJ, Wooley J, Pollock BD, Mahoney C, et al. Albumin is predictive of 1-year mortality after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2018; 106: 1302-7. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.06.024 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.06.024 PMid:30048632 |

||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER