From risk stratification to precision care: what is new in the 2025 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease and pregnancy

EDITORIALS

From risk stratification to precision care: what is new in the 2025 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease and pregnancy

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2025.600

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 12/10/2025

- Received: 08/10/2025

- Accepted: 08/10/2025

- Views: 7855

- Downloads: 1053

- Keywords: Heart diseases, maternal health services, practice guideline, pregnancy, risk assessment

Address for Correspondence: Zhenisgul Tlegenova, Department of Internal Diseases 2, West Kazakhstan Marat Ospanov Medical University, Aktobe, Kazakhstan

Email: zhenisgul.tlegenova@zkmu.kz Mobile: +7 707 4998565

ORCID: Zhenisgul Tlegenova –0000-0002-3707-7365; Aiganym Amanova - 0009-0001-9787-7583; Bekbolat Zholdin - 0000-0002-4245-9501

Zhenisgul Tlegenova*, Aiganym Amanova, Bekbolat Zholdin

Department of Internal Diseases 2, West Kazakhstan Marat Ospanov Medical University, Aktobe, Kazakhstan

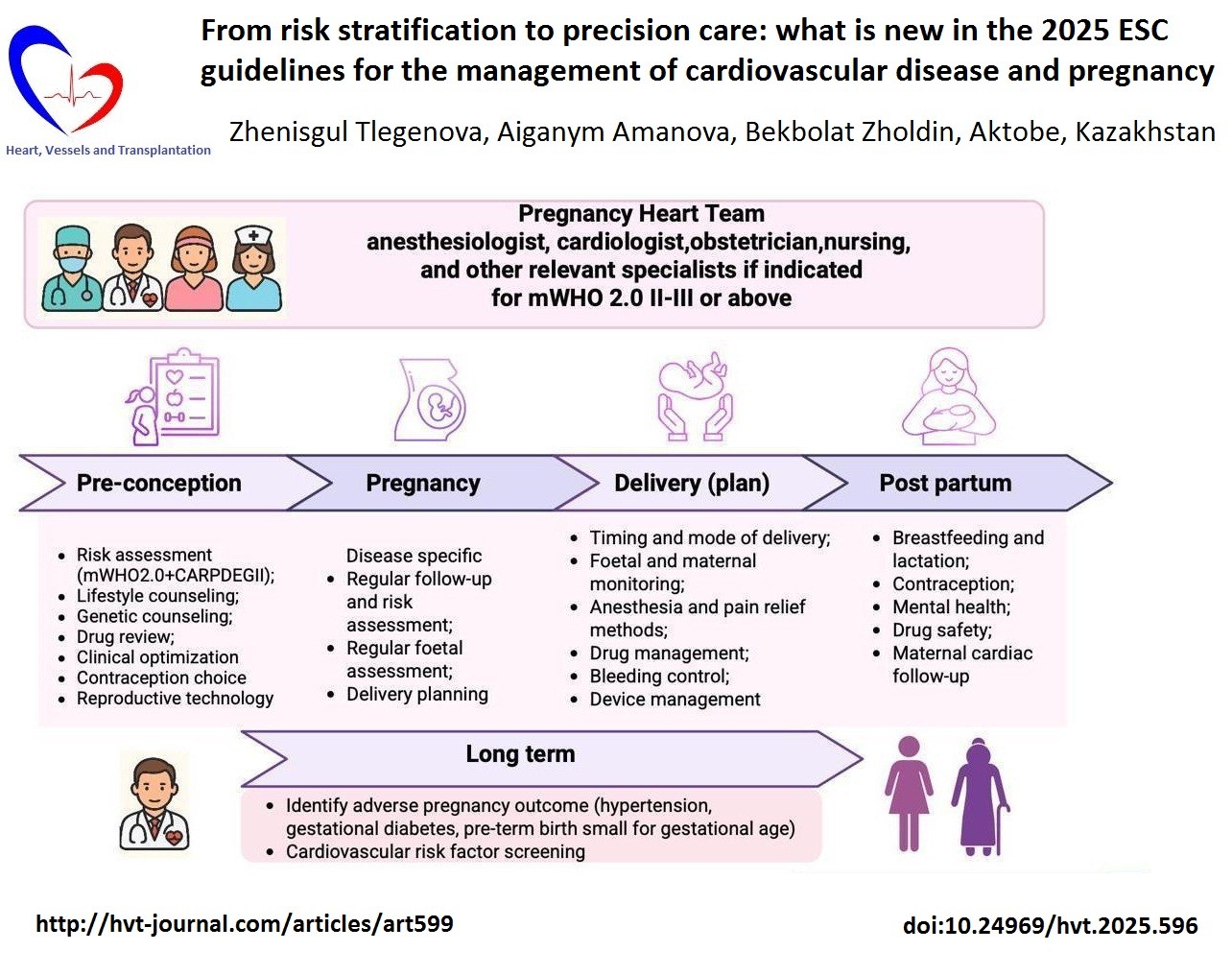

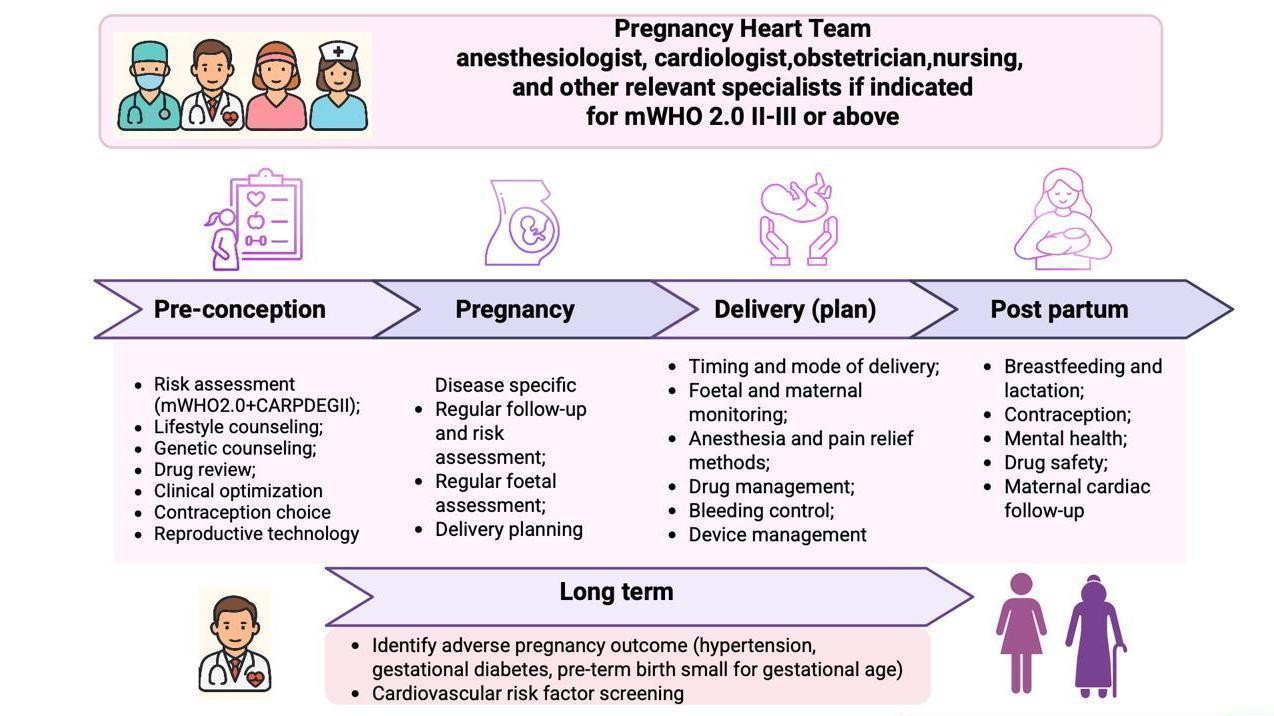

Graphical abstract

Key words: Heart diseases, maternal health services, practice guideline, pregnancy, risk assessment

Maternal cardiovascular disease (CVD) has emerged as one of the most significant challenges in contemporary obstetric and cardiovascular medicine across high-, middle-, and low-income countries [1). Demographic transitions— including increasing maternal age at first pregnancy, improved survival of women with congenital heart disease into adulthood, and the global rise in hypertension, diabetes, and obesity have collectively contributed to this trend (2).

Adding to this complexity, the growing use of assisted reproductive technologies has been associated with a higher incidence of cardiovascular complications (3).

Even in otherwise healthy women, pregnancy induces profound hemodynamic adaptation, including expansion of blood volume, increased cardiac output, reduced systemic vascular resistance, venous compression, anemia, and blood pressure variability. These physiological changes may unmask or exacerbate preexisting cardiovascular conditions (4)

Registry data indicate that cardiovascular complications occur in approximately 16% of pregnant women with pre-existing heart disease. Even among those classified as low risk, the incidence remains around 5% (5, 6).

The spectrum of maternal CVD is broad, encompassing congenital and inherited cardiac disorders, aortopathies, and valvular disease, as well as acquired or pregnancy-induced conditions such as preeclampsia, peripartum cardiomyopathy, venous thromboembolism (VTE), acute coronary syndromes (ACS), and arrhythmias (7).

Early risk assessment, comprehensive preconception counseling, and structured longitudinal follow-up throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period are therefore essential to improving maternal outcomes. In this context, the 2025 ESC Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease in Pregnancy (8) represent a major conceptual and practical advance. The present editorial provides a concise and clinically relevant overview of the most important updates, emphasizing their implications for multidisciplinary care and long-term maternal cardiovascular health.

The Pregnancy Heart Team (PHT) is established as the standard of care for women with moderate to very high cardiovascular risk (mWHO 2.0 class II–III or higher). The PHT—comprising cardiologists, obstetricians, anesthesiologists, nurses, and additional specialists as required—provides coordinated management from preconception counseling through delivery and up to six months postpartum (Fig. 1). This transition from episodic consultations to structured, longitudinal care aligns maternal cardiology with contemporary multidisciplinary models that promote integration, continuity, and patient-centered management across all levels of cardiovascular care. The structure of the PHT is flexible, allowing for the inclusion of additional experts when clinically indicated. For instance, in pregnant women with cancer requiring cardiotoxic cancer therapy, close collaboration between the PHT and a cardio-oncology specialist is recommended (Class I, Level C) (8).

Figure 1. The Pregnancy Heart Team model of integrated care

The updated mWHO 2.0 classification represents one of the most significant conceptual advances introduced in the 2025 Guidelines. This revised framework offers greater diagnostic precision and broader disease representation compared with the 2018 version, now encompassing ventricular dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathies, aortopathies, valvular disease, and both congenital and acquired coronary disorders. The mWHO 2.0 categories define a structured model of care: I – standard obstetric management; II – cardiology follow-up, PHT not routinely required; II–III – individualized management, PHT often advised; III – high risk, mandatory PHT oversight; IV – pregnancy no longer labeled «absolutely contraindicated», but requires shared decision-making within the PHT, including detailed maternal–fetal risk counseling, psychological support, and maximally safe monitoring if pregnancy continues. The classification now incorporates the CARPREG II prognostic model, which improves the accuracy of maternal cardiac risk assessment. Key management aspects, including preconception counseling, individualized monitoring strategies during pregnancy, birth planning, and postpartum care, are guided by a structured, evidence- based framework that ensures patient-centered care (Fig. 1) (8).

Hypertension remains one of the most common cardiovascular complications in pregnancy. Women with blood pressure exceeding 160/110 mmHg should be hospitalized for urgent management. For acute treatment intravenous labetalol, urapidil, or nicardipine, as well as short-acting nifedipine are preferred agents (IC). For maintenance therapy, methyldopa (IB), labetalol, metoprolol, and dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (IC) remain first options with a target BP below 140/90 mmHg (IB). The soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 to placental growth factor (sFlt-1/PlGF) ratio provides a biomarker-based approach for differentiating preeclampsia from other hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. A ratio ≥85 or PIGF <12 pg/ml indicates a high likelihood of placental dysfunction and imminent preeclampsia, warranting hospitalization and close monitoring. Conversely, when the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio is <38 the development of preeclampsia within the next 7 days can be reliably excluded, allowing safe outpatient management in stable women (8).

Peripartum cardiomyopathy is now addressed in a dedicated section, highlighting the importance of early detection, detailed risk evaluation, and genetic counseling with testing to identify pathogenic variants that may guide prognosis, therapeutic decisions and counseling for future pregnancies (IIaC) (8).

Biomarkers such as BNP and NT-proBNP are recommended before pregnancy in women with heart failure of any etiology - including prior peripartum cardiomyopathy, cardiomyopathy, adult congenital heart disease, and pulmonary hypertension, and should be monitored during pregnancy according to disease severity or new-onset symptoms (IIaB). Measurement of natriuretic peptide levels at baseline and during anthracycline therapy may also be considered in pregnant women with cancer (IIbC) (8).

For suspected VTE, a pregnancy-adapted YEARS algorithm with adjusted D-dimer thresholds is recommended. Key steps include immediate initiation of therapeutic low molecular weight heparin until VTE is confirmed or excluded (IIaC), compression ultrasound as first-line imaging, and computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiography if results remain inconclusive (IIa). Postpartum, anticoagulation should continue for at least six weeks (up to three months), unless lifelong therapy is indicated. This algorithm reduces unnecessary radiation exposure while maintaining diagnostic accuracy (8).

Pregnant women presenting with chest pain require prompt exclusion of life-threatening causes, including pulmonary embolism, ACS (notably spontaneous coronary artery dissection), and acute aortic syndrome (IC). When clinically indicated, emergency percutaneous coronary intervention should be performed without delay, following the same principles as in non-pregnant patients, to ensure optimal maternal outcomes (Class I, Level C). If dual antiplatelet therapy is necessary, clopidogrel is preferred, with treatment duration similar to that in non-pregnant patients (IC). Statins may be continued in selected high-risk women with familial hypercholesterolemia or established atherosclerotic disease (IIbC). PCSK9 inhibitors, ezetimibe, and bempedoic acid remain not recommended due to insufficient safety data (8).

Echocardiography and non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging are the preferred diagnostic tools during pregnancy. Transthoracic echocardiography is indicated for any new or unexplained cardiovascular symptoms. Ionizing radiation must follow the ALARA principle (IC), keeping fetal doses below 50 mGy (IC). CT or nuclear imaging should be reserved for life-threatening indications, preferably after 12 weeks of gestation (8).

Vaginal delivery remains the preferred mode in most women with CVD. Cesarean section is reserved for obstetric or specific cardiac indications, including ejection fraction ≤30%, NYHA class III–IV, uncontrolled arrhythmia, severe left ventricular outflow obstruction, or ongoing vitamin K antagonist therapy. Postpartum surveillance extends to six months, recognizing the delayed risk of decompensation and arrhythmic events (8).

A new visual drug safety matrix provides a user-friendly overview of medication safety during pregnancy and lactation. It classifies drugs as recommended (first choice), second choice, or contraindicated (evidence of fetal infant toxicity or no data on safety), facilitating rapid, evidence-based decision-making. Agents such as angiotension-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors, mineralcorticoid receptor antagonists, sodium glucose co-transporter -2 inhibitors, direct oral anticoagulants, atenolol, ivabradine, amiodarone, mavacamten, bosentan, ambrisentan, riociguat, vericiguat, selexipag remain contraindicated. While, methyldopa, labetalol, metoprolol, nifedipine, amlodipine are validated as safe first-line antihypertensives, while beta-blockers such as metoprolol, carvedilol, labetolol are preferred in heart failure. The matrix also details drug safety profiles during lactation, supporting consistency and safety in postpartum pharmacotherapy (8).

Pregnancy is conceptualized as a «cardiovascular stress test». Adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs) - including preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, and fetal growth restriction - are recognized as early markers of future CVD. The guidelines call for structured long-term surveillance and preventive counseling, and cardiovascular risk factor screening for all women with a history of APOs (8).

Conclusion

The ESC 2025 Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease in Pregnancy mark a paradigm shift toward individualized, multidisciplinary, and lifelong cardiovascular care for women. They equip clinicians with practical, evidence-based tools for optimizing maternal and fetal outcomes, emphasizing early risk stratification, biomarker-guided diagnostics, and postnatal prevention. For researchers, these guidelines highlight emerging priorities - such as genetic testing, long-term outcomes, and implementation science - laying the foundation for the next decade of innovation in maternal cardiovascular medicine.

Peer-review: Internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: Zh. T, A.A. and B. Z. equally contributed to manuscript preparation and fulfilled the authorship criteria

Acknowledgements and funding: None to declare

Statement on A.I.-assisted technologies use: Editorial assistance for language and grammar refinement was provided using ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA). The authors retain full responsibility for the scientific content and interpretation.

Data and material availability: Does not apply

References

| 1.Mehta LS, Warnes CA, Bradley E, Burton T, Economy K, Mehran R, et al.; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Stroke Council. Cardiovascular considerations in caring for pregnant patients: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020; 141: e884-e903. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000772 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000772 |

||||

| 2.Lundborg L, Ananth CV, Joseph KS, Cnattingius S, Razaz N. Changes in the prevalence of maternal chronic conditions during pregnancy: A nationwide age-period-cohort analysis. BJOG 2025; 132: 44-52. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17885 https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17885 PMid:38899437 PMCid:PMC11612608 |

||||

| 3.Mauricio R, Sharma G, Lewey J, Tompkins R, Plowden T, Rexrode K, et al; American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in Women and Underrepresented Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young. Assessing and addressing cardiovascular and obstetric risks in patients undergoing assisted reproductive technology: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025; 151: e661-e676. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001292 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001292 PMid:39811953 |

||||

| 4.Ouzounian JG, Elkayam U. Physiologic changes during normal pregnancy and delivery. Cardiol Clin 2012; 30: 317-29. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2012.05.004 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2012.05.004 PMid:22813360 |

||||

| 5.Roos-Hesselink J, Baris L, Johnson M, De Backer J, Otto C, Marelli A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with cardiovascular disease: evolving trends over 10 years in the ESC Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac disease (ROPAC). Eur Heart J 2019; 40: 3848-55. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz136 https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz136 PMid:30907409 |

||||

| 6.Silversides CK, Grewal J, Mason J, Sermer M, Kiess M, Rychel V, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with heart disease: The CARPREG II Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 2419-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.076 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.076 PMid:29793631 |

||||

| 7.Keepanasseril A, Pfaller B, Metcalfe A, Siu SC, Davis MB, Silversides CK. Cardiovascular deaths in pregnancy: growing concerns and preventive strategies. Can J Cardiol 2021; 37: 1969-78. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.09.022 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2021.09.022 PMid:34600086 |

||||

| 8.De Backer J, Haugaa KH, Hasselberg NE, de Hosson M, Brida M, Castelletti S, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2025 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease and pregnancy. Eur Heart J 2025:ehaf193. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf193 https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf193 PMid:40878294 |

||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER