Case of Williams-Beuren syndrome presenting with recurrent atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia managed with electrophysiological study and radiofrequency ablation

CASE REPORT

Case of Williams-Beuren syndrome presenting with recurrent atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia managed with electrophysiological study and radiofrequency ablation

Article Summary

- DOI: 10.24969/hvt.2026.626

- CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

- Published: 22/02/2026

- Received: 31/12/2025

- Revised: 15/02/2026

- Accepted: 16/02/2026

- Views: 36

- Downloads: 18

- Keywords: Williams-Beuren syndrome, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, electrophysiological study, radiofrequency ablation, supravalvular aortic stenosis

Address for Correspondence: Sanket Bari, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Hospital And Research Centre, Pimpri, Pune-018, Maharashtra, India

Email: sanketbari88@gmail.com

ORCID: Chetan Bhole - 0009-0005-4743-1400; Atharva Telhande - 0009-0008-2568-9891; Sanket Bari- 0009-0004-3087-8444

Chetan Bhole1, Atharva Telhande2, Sanket Bari1

1Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Hospital And Research Centre, Pimpri, Pune-018

Maharashtra, India

2N.K.P Salve Institute Of Medical Sciences And Research Center And Lata Mangeshkar Hospital, Nagpur, Maharashtra, 440019, India

Abstract

Objective: Williams-Beuren syndrome (WBS) carries markedly elevated sudden cardiac death risk primarily from structural cardiovascular anomalies and QTc prolongation. Supraventricular tachycardias, particularly atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT), remain unreported.

Case presentation: A young adult in twenties with genetically confirmed WBS (7q11.23 deletion) and supravalvular aortic stenosis (SVAS) presented with recurrent palpitations. Electrocardiogram documented narrow-complex tachycardia (180 bpm, short RP interval <70 ms) diagnostic of typical slow-fast AVNRT. Evaluation prompted electrophysiological study that confirmed recurrent paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, typical slow fast AVNRT. Radiofrequency ablation of the slow pathway was achieved without complications.

Conclusion: This represents the first documented electrophysiological study confirmed AVNRT in WBS. Early electrophysiological study and catheter ablation provide safe, curative therapy even amid structural heart disease and coronary anomaly risks.

Key words: Williams-Beuren syndrome, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, electrophysiological study, radiofrequency ablation, supravalvular aortic stenosis

Introduction

Williams-Beuren syndrome results from heterozygous microdeletion at chromosome 7q11.23 encompassing 26-28 genes including elastin (ELN), affecting approximately 1 in 7500 live births (1, 2). Cardiovascular manifestations occur in 80% of patients, predominantly supravalvular aortic stenosis (SVAS, 50-75%) and peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis (up to 40%) (2, 3). These patients face profoundly elevated sudden cardiac death risk (25-100 times general population; 1 per 1000 patient-years) attributable to elastin arteriopathy, coronary ostial stenosis (20-30%), left ventricular hypertrophy from chronic pressure overload, and QTc prolongation (prevalence 13-50%) (3-5).

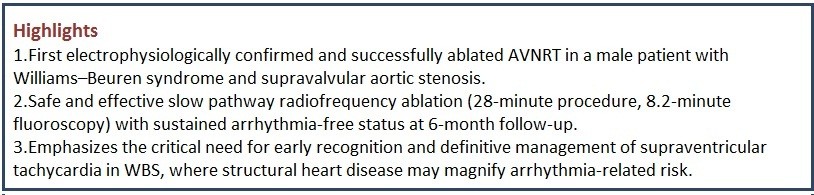

Graphical abstract

While atrial arrhythmias occur in 12% and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome has been documented, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT) remains unreported in comprehensive literature reviews (1, 6).

Our aim is to report the first electrophysiologically-confirmed case of atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia in a young adult with genetically confirmed Williams-Beuren syndrome and supravalvular aortic stenosis, demonstrating the safety and efficacy of slow pathway radiofrequency ablation despite elevated sudden cardiac death risks.

Case report

A young male in his twenties with genetically confirmed Williams-Beuren syndrome (heterozygous 7q11.23 deletion spanning 26 genes) (1) and known SVAS presented with recurrent episodes of palpitations lasting 10-30 minutes, occurring 2 to 3 times in last 6 months. Episodes were associated with mild dizziness but no syncope, chest pain, exertional dyspnea. No history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercalcemia, thyroid dysfunction, or renal impairment was noted. Family history was negative for arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death. The patient experienced multiple hospital admissions for lower respiratory tract infections during infancy & early childhood with global developmental delay.

Written informed consent was obtained from patient and guardian for procedures, treatment and publication of case with pictures.

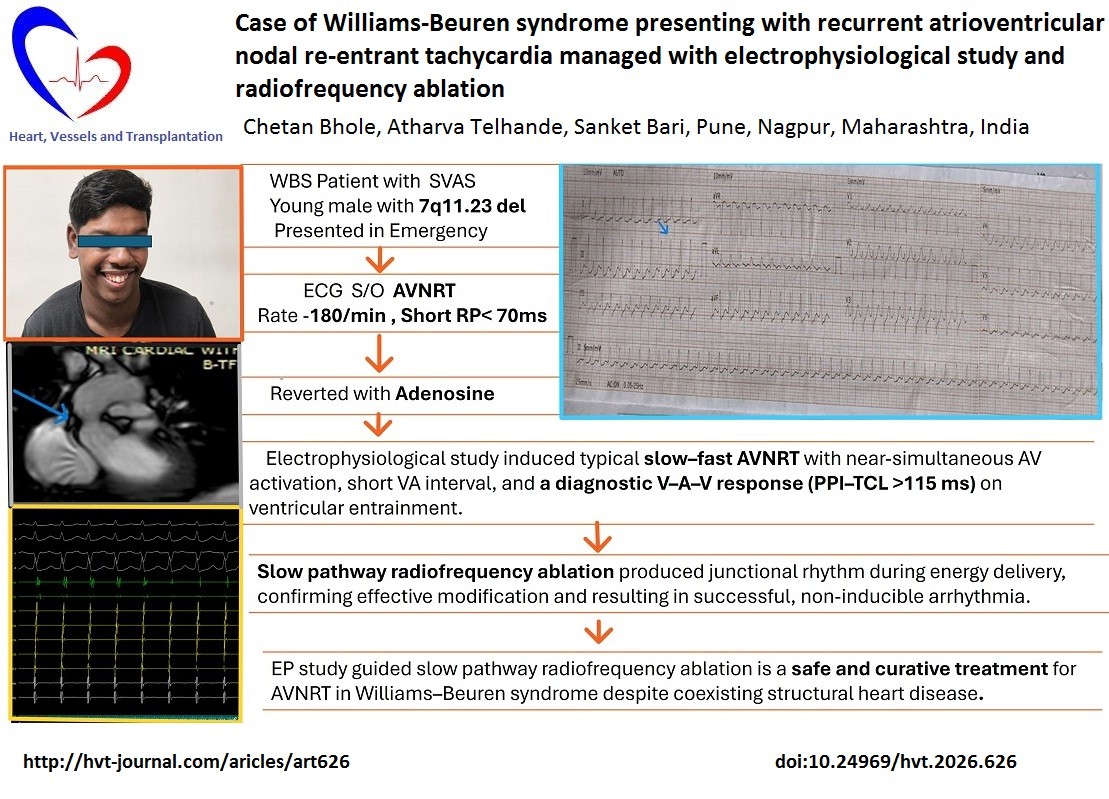

On physical examination, patient had classical Williams-Beuren syndrome dysmorphic features including broad forehead, periorbital fullness and full lower lip (Fig. 1).

Laboratory evaluation including renal, hepatic, thyroid function, and serum calcium was normal. Blood reports showed dyslipidemia (low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol 133 mg/dL, triglycerides 273 mg/dL) that was managed by medical treatment.

Cardiovascular examination revealed grade 3/6 ejection systolic murmur maximal at right second intercostal space, consistent with SVAS. Respiratory, abdominal examinations were unremarkable.

Figure 1. Clinical photograph illustrating classic facial features of Williams-Beuren syndrome, including broad forehead, periorbital puffiness (fullness around the eyes), bulbous nasal tip, full cheeks with malar flattening (flat cheekbones), wide mouth, and prominent lips (particularly the lower lip). These distinctive "elfin facies" are commonly associated with this genetic disorder

(Written permission was obtained from a patient for publication of pictures.)

Genetic evaluation confirmed Williams–Beuren syndrome, and SVAS was identified on cardiovascular imaging and was managed conservatively with periodic surveillance.

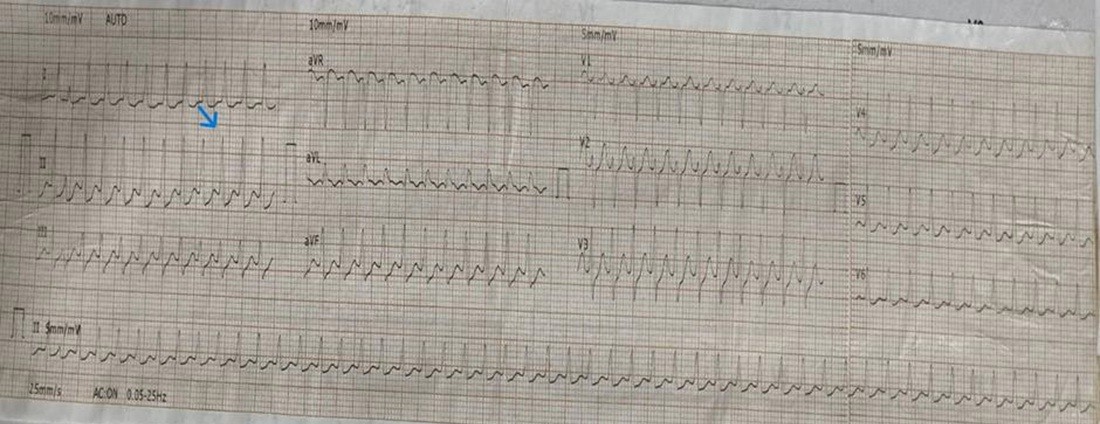

During symptomatic episodes, 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated regular narrow-complex tachycardia at 180 beats per minute with short RP interval (<70 ms) and 1:1 atrioventricular relationship (Fig. 2) which was terminated with adenosine. Post tachycardia termination ECG showed normal sinus rhythm without pre-excitation or QTc prolongation.

Figure 2. The 12-lead ECG demonstrating typical atrioventricular nodal re-entrant (slow–fast AVNRT).

ECG shows a regular narrow-complex tachycardia. A pseudo S wave is visible in the inferior lead (blue arrow), representing retrograde atrial activation. The RP interval is short (< 70 ms), consistent with short-RP tachycardia and typical AVNRT.

AVNRT - atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, ECG – electrocardiogram

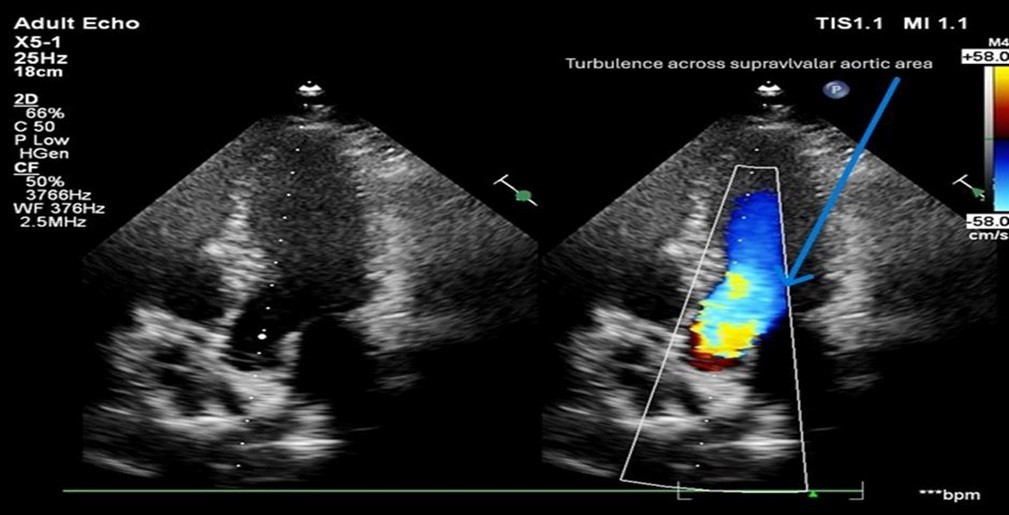

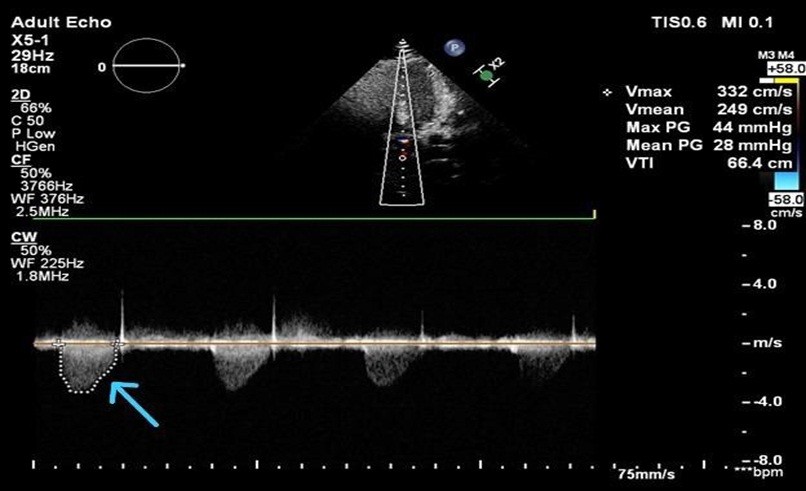

Cardiovascular imaging (echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonce imaging, cMRI) confirmed SVAS. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed situs solitus, levocardia, supravalvular aortic gradient 44 mmHg, and mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (Fig. 3, 4).

Figure 3. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrating supravalvular aortic turbulence.

Apical five-chamber view showing left ventricular outflow tract and ascending aorta (left), and color Doppler imaging (right) demonstrating mosaic turbulent flow across the supravalvular aortic region (arrow), consistent with flow acceleration at the level of supravalvular aortic narrowing.

Figure 4. Transthoracic echocardiography (apical view) with continuous-wave Doppler interrogation of the left ventricular outflow tract demonstrating high-velocity systolic flow across the supravalvular aortic region (arrow). Peak velocity (Vmax) is 3.32 m/s with a calculated peak pressure gradient of 44 mmHg and mean gradient of 28 mmHg, consistent with hemodynamically significant supravalvular aortic stenosis.

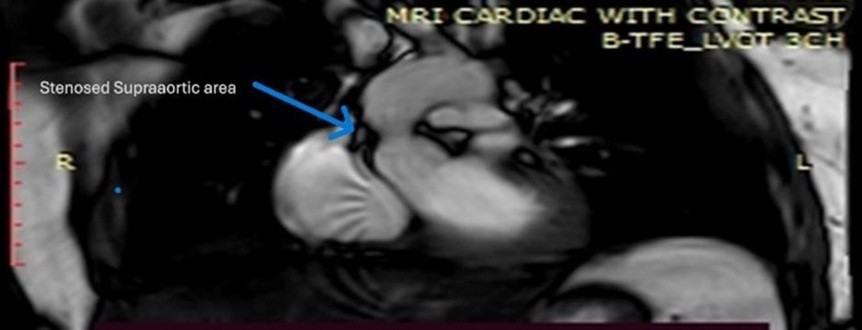

Magnetic resonance imaging also displayed findings consistent with SVAS (Fig. 5).

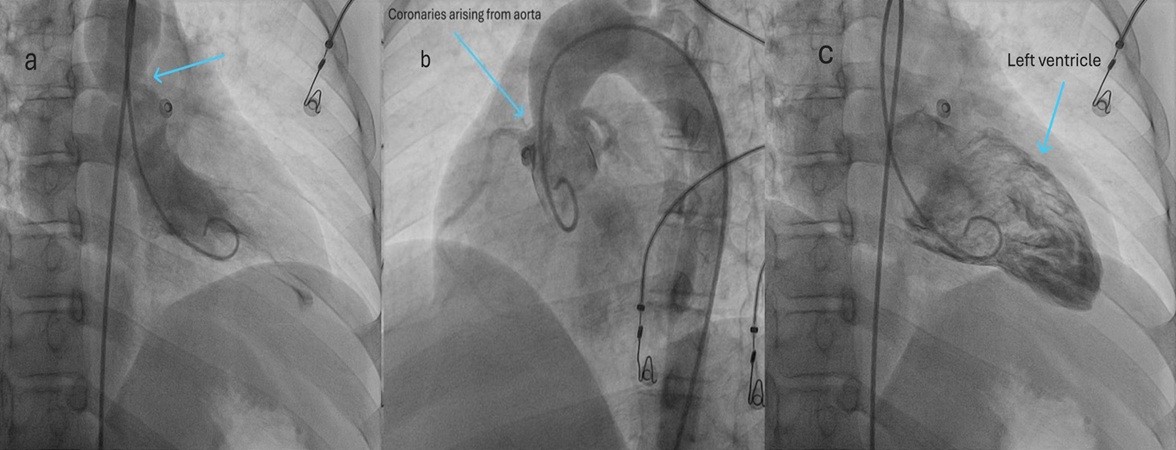

Left ventricular angiogram showed SVAS and normal origin of coronary arteries (Fig. 6).

Figure 5. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing focal narrowing at the supravalvular aortic region (blue arrow) above the aortic valve, consistent with supravalvular aortic stenosis

Figure 6. (a) Systolic left ventricular angiogram demonstrates narrowed supravalvular aortic segment (arrow) consistent with supravalvular aortic stenosis, with pigtail catheter positioned in the ascending aorta; (b) Normal origin of coronary arteries from the aortic root proximal to the stenosis arrow), confirming appropriate coronary anatomy; (c) Left ventriculogram of the left ventricle with preserved cavity outline.

Following multidisciplinary discussion (cardiology, clinical electrophysiology, cardiac imaging, medical genetics, endocrinology), definitive electrophysiological (EP) study was recommended.

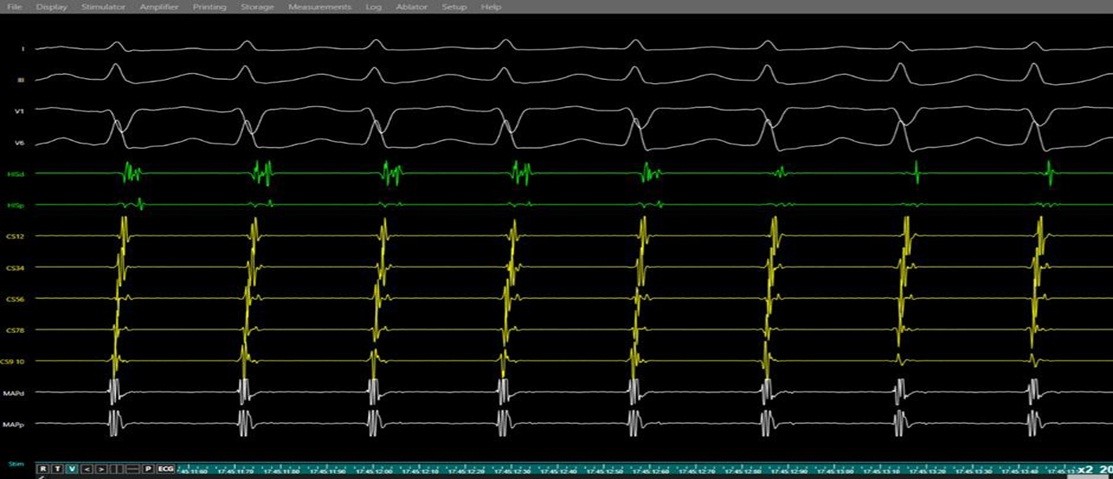

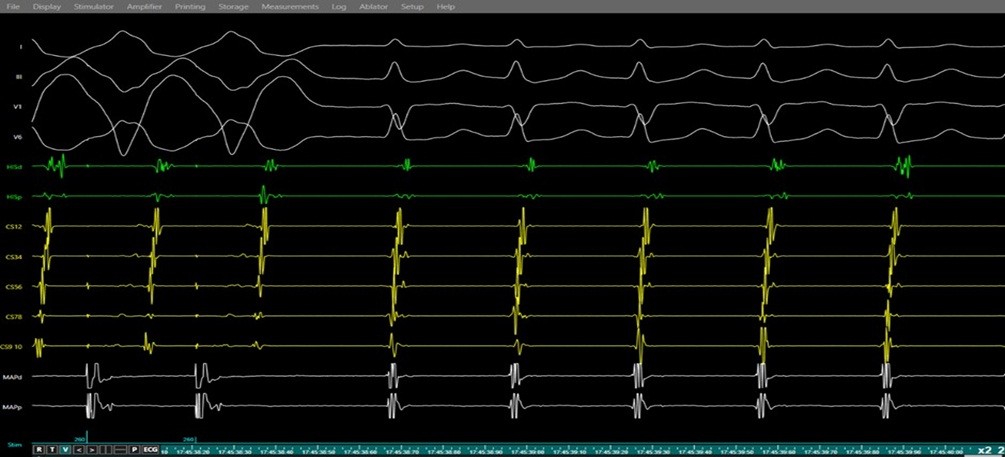

Intracardiac recordings confirmed dual atrioventricular nodal physiology with AH jump. Programmed atrial stimulation (S1S2 400/260 ms) reproducibly induced typical slow-fast AVNRT. Tachycardia diagnosis was validated by ventricular entrainment demonstrating post-pacing interval minus tachycardia cycle length of >115 ms and VAV response. Radiofrequency ablation (45 watts, 55°C, 10 seconds) of slow pathway region produced junctional rhythm confirming correct slow pathway localisation. Further consolidation lesions were applied. Post radiofrequency ablation , no tachycardia was induced despite aggressive PES protocol and isoprenaline suggestive of successful slow pathway ablation. Total procedure duration was 28 minutes with fluoroscopy time of 8.2 minutes (Fig. 7-9). No acute complications occurred.

Figure 7. Induction of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) during electrophysiology study.

Simultaneous surface electrocardiogram (leads I, II, V1, V6) and intracardiac electrograms (His bundle region, and coronary sinus, right ventricle) demonstration of a regular narrow-complex tachycardia with near-simultaneous atrial and ventricular activation and a short VA interval, consistent with typical atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia.

Figure 8. Entrainment response during electrophysiology study confirming AVNRT.

Simultaneous surface ECG (leads I, II, V1, V6) and intracardiac electrograms (His bundle region, coronary sinus, and right ventricular channel) demonstrating ventricular overdrive pacing during ongoing SVT. The tracings show a V–A– V response upon cessation of pacing with a long post-pacing interval–tachycardia cycle length > 115ms (PPI–TCL) difference, consistent with typical AVNRT and excluding atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) and atrial tachycardia.

AVNRT - atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, ECG – electrocardiogram

Figure 9. Junctional rhythm during slow pathway ablation

Simultaneous surface ECG (leads I, II, V1, V6) and intracardiac electrograms (coronary sinus, and ablation catheter) demonstrating junctional rhythm occurring during radiofrequency energy delivery at the slow pathway region a marker of effective slow pathway modification during AVNRT ablation.

AVNRT - atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, ECG – electrocardiogram

The patient was discharged and counseling was provided regarding dyslipidemia management and lifelong cardiovascular surveillance given persistent SVAS and Williams-Beuren syndrome associated sudden death risk (5). The patient remained arrhythmia-free during 1, 3, and 6-month clinic visits. Serial 12-lead ECGs demonstrated normal sinus rhythm.

Discussion

This case represents the rare EP study confirmed and successfully ablated AVNRT in Williams-Beuren syndrome, distinguishing it from previously documented arrhythmias (Table 1) (1, 4, 6).

|

Table 1. Reported arrhythmias in Williams-Beuren syndrome |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arrhythmia type |

Age group |

Structural Disease |

Management |

Reference |

|

QTc prolongation |

All ages |

SVAS, LVH |

Surveillance, β-blockers |

Collins RT 2011 (4) |

|

WPW syndrome |

Pediatric |

SVAS |

EP study/ablation |

Karadeniz C 2024 (6) |

|

Atrial tachycardia |

Pediatric |

Pulmonary stenosis |

Medical therapy |

Sharma P 2015 (1) |

|

AVNRT |

Young adult |

SVAS |

EP study/RFA |

Present case |

|

AVNRT- atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, EP – electrophysiological, LVH- left ventricular hypertrophy, RFA – radiofrequency ablation, SVAS – supravalvular aortic stenosis, WPW- Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome |

||||

While AVNRT prevalence likely parallels the general population (0.5-2% in adults) and its clinical significance becomes profoundly amplified in Williams-Beuren syndrome due to unique anatomical and physiological vulnerabilities (7).

Tachycardia rates of 180-220 bpm characteristic of AVNRT precipitate acute hemodynamic compromise by impairing diastolic filling across the fixed SVAS obstruction (3). This reduces stroke volume and coronary perfusion pressure, along with baseline left ventricular hypertrophy and potential QTc prolongation (13-50% prevalence) (4). Resultant myocardial ischemia, systemic hypotension, or cerebral hypoperfusion could precipitate syncope or sudden death—already 25-100 times more likely (1 per 1000 patient-years) in Williams-Beuren syndrome (5). The young age and relatively subtle symptomatology in our patient underscore diagnostic challenges; adenosine termination provided crucial diagnostic clarity prompting definitive therapy.

Comprehensive review of 12 studies spanning continents (India n=43 patients, Africa, Turkey, global registries) identified no prior AVNRT cases (1, 4, 6, 8-11). Documented arrhythmias include atrial tachycardia (12%) (1), Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (rare ablation cases) (6), and QTc prolongation requiring surveillance and beta-blockade (4).

This report provides novel incremental value by demonstrating EP study safety and radiofrequency ablation efficacy (>95% acute success, >90% long-term) despite Williams-Beuren syndrome -specific coronary risks including ostial stenosis (20-30%) and elastin arteriopathy (3). Pre procedural left ventriculogram confirmed supravalvular aortic stenosis. Fluoroscopy time was minimized (8.2 minutes). Slow pathway modification, rather than complete elimination, successfully abolished the arrhythmic substrate while preserving atrioventricular nodal function. An arrhythmia-free six-month follow-up with normal serial ECGs supports the durability of this approach.

The 7q11.23 microdeletion lacks genes directly regulating atrioventricular nodal physiology (e.g., CACNA1C resides outside deletion) (2). However, contiguous gene haploinsufficiency (LIMK1, CLIP2) may contribute to autonomic dysregulation alongside systemic elastin arteriopathy creating arrhythmia substrate (11). Supraventricular tachycardias likely serve as precipitating factors in the presence of structural vulnerabilities rather than representing primary genetic associations. The observed mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy from chronic supravalvular aortic stenosis–related pressure overload further amplifies the risk of ischemia during rapid heart rates (3, 12).

The genetic diagnosis prompted detailed clinical evaluation to exclude hypercalcemia, renal anomalies, and thyroid dysfunction, which can influence the occurrence of arrhythmias (8, 10).

This case establishes EP study with radiofrequency ablation as safe, curative therapy for AVNRT in Williams-Beuren syndrome. Clinicians managing Williams-Beuren syndrome patients with palpitations should maintain high suspicion for supraventricular tachycardias.

Conclusion

Williams-Beuren syndrome mandates vigilant arrhythmia surveillance given profound sudden cardiac death predisposition (5). This confirmed AVNRT case by electrophysiology study affirms catheter ablation as safe, curative therapy despite coexisting structural heart disease. The amplified hemodynamic consequences of supraventricular tachycardia across SVAS obstruction necessitate high clinical suspicion, systematic diagnostic evaluation, and early specialist referral to mitigate potentially catastrophic outcomes.

Ethics: Institutional approval was obtained.

Written informed consent was obtained from patient and guardian for procedures, treatment and publication of case with pictures.

Peer-review: External and internal

Conflict of interest: None to declare

Authorship: C.B., A.T., and S.B. equally contributed to case management and preparation of case report, thus fulfilled all authorship criteria

Acknowledgements and funding: None to declare

Statement on A.I.-assisted technologies use: We declare that we did not use AI-assisted technologies in preparation of this manuscript

Data and material availability: Does not apply

References

| 1.Sharma P, Gupta N, Chowdhury MR, Phadke SR, Sapra S, Halder A, et al. Williams-Beuren syndrome: experience of 43 patients and a report of an atypical case from a tertiary care center in India. Cytogenet Genome Res 2015; 146: 187-94. doi:10.1159/000437243 https://doi.org/10.1159/000437243 PMid:26414007 |

||||

| 2.Morris CA. Williams syndrome. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2024. PMID:20301394. | ||||

| 3.Collins RT 2nd. Cardiovascular disease in Williams syndrome. Circulation 2013; 127: 2125-34. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000064 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000064 PMid:23716381 |

||||

| 4.Collins RT 2nd. Clinical significance of prolonged QTc interval in Williams syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108: 471-3. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.03.078 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.03.078 PMid:21624552 PMCid:PMC3159191 |

||||

| 5.Wessel A, Gravenhorst V, Buchhorn R, Gravinghoff L, Buchhorn K. Risk of sudden death in the Williams-Beuren syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2004; 127A: 234-7. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.30014 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.30014 PMid:15150787 |

||||

| 6.Karadeniz C, Yıldız K, Öksüz S, Keçici RN, Çoğulu Ö. A case of Williams syndrome with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Birth Defects Res 2024; 116: e2305. doi:10.1002/bdr2.2305 https://doi.org/10.1002/bdr2.2305 PMid:38411336 |

||||

| 7.Meng H, Jia YX, Yang HM, Gao X, Li CGH, Xin GY, et al. A case report of Williams syndrome with main clinical manifestation of hypercalcemia and gastrointestinal bleeding, and with an accompanying literature review. Brain Behav 2023; 13: e3086. doi:10.1002/brb3.3086 https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.3086 |

||||

| 8.Abidi K, Jellouli M, Ben Rabeh R, Hammi Y, Gargah T. Williams-Beuren syndrome associated with single kidney and nephrocalcinosis: a case report. Pan Afr Med J 2015; 22: 276. doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.22.276.7443 https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2015.22.276.7929 |

||||

| 9.Mapelli M, Zagni P, Calbi V, Twalib A, Ferrara R, Agostoni P. A case of Williams syndrome in a Ugandan child: a feasible diagnosis even in a low-resource setting. Children (Basel) 2021; 8: 1192. doi:10.3390/children8121192 https://doi.org/10.3390/children8121192 PMid:34943388 PMCid:PMC8700345 |

||||

| 10.Koren I, Kessel I, Rotschild A, Cohen-Kerem R. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis and hypothyroidism as presenting symptoms of Williams-Beuren syndrome: a case report. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2015; 79: 1582-3. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.06.002 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.06.002 PMid:26104479 |

||||

| 11.Parlak M, Nur BG, Mihçı E, Durmaz E, Karaüzüm SB, Akcurin S, et al. Clinical expression of familial Williams-Beuren syndrome in a Turkish family. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2014; 27: 153-8. doi:10.1515/jpem-2013-0164 https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2013-0167 PMid:24057591 |

||||

| 12.Nomura K, Moronuki T, Takeuchi S, Maeda T, Toda K, Kobayashi T. Role of transthoracic echocardiography in early diagnosis of Williams syndrome in the neonatal period. CASE (Phila) 2022; 6: 462-6. doi:10.1016/j.case.2022.09.002 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.case.2022.09.002 PMid:36861100 PMCid:PMC9968873 |

||||

Copyright

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

AUTHOR'S CORNER